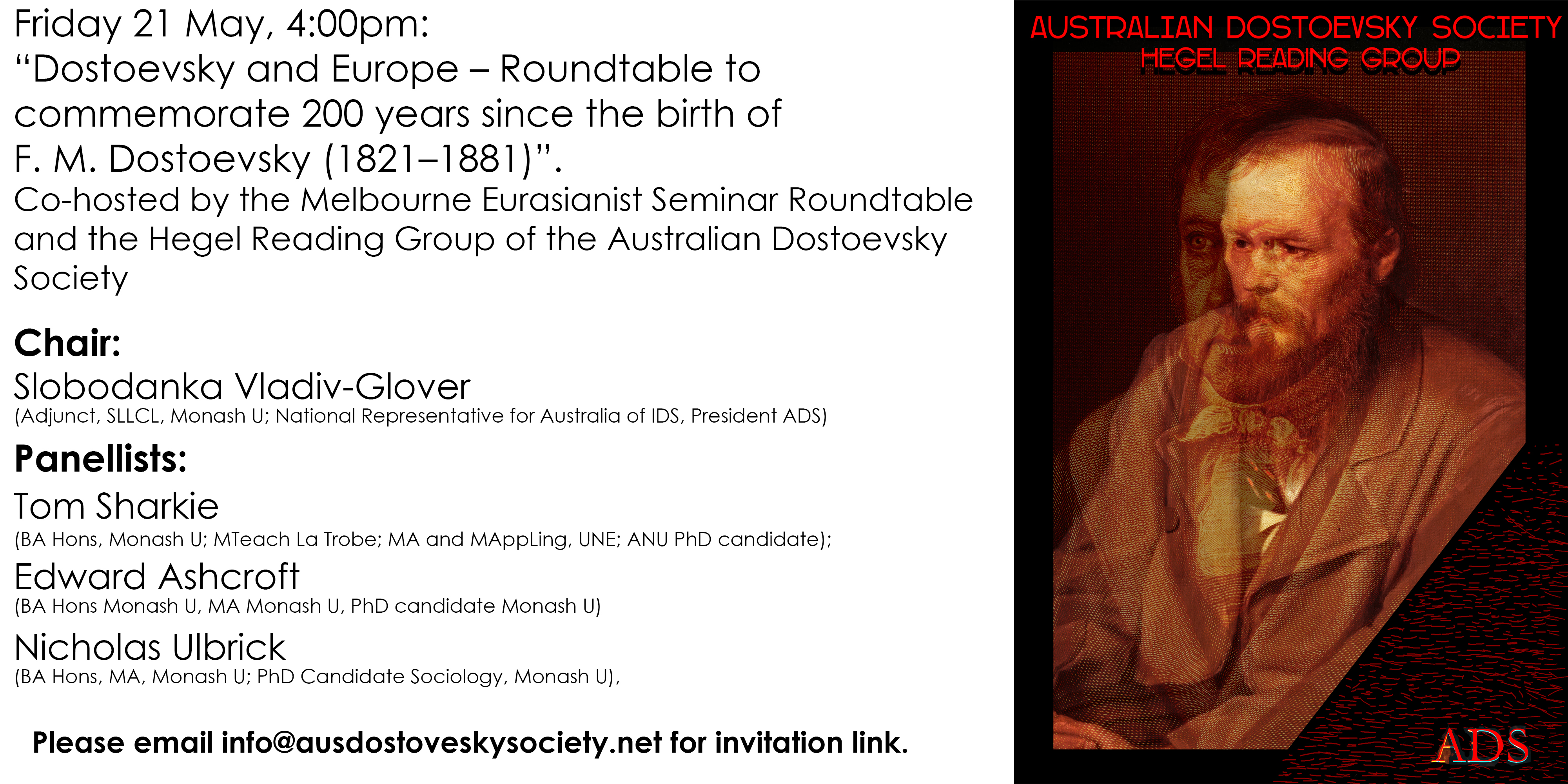

Australian Dostoevsky Society

Vladiv-Glover, M.(Fellow) School of Languages, Literature, Cultures and Linguistics Activity: External Academic Engagement › Professional association or peak discipline body

Menu

Vladiv-Glover, M.(Fellow) School of Languages, Literature, Cultures and Linguistics Activity: External Academic Engagement › Professional association or peak discipline body

Participants: Richard Stewart, Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, Nikolai Gladanac

Discussant: Nicholas Ulbrick

Saturday, 2 March 2024, 2pm–4pm AUS EST.

Dostoevsky’s artistic universe manifests as a non-Euclidian world, in which characters move in a temporality of apocalyptic time or time out of time. Dostoevsky’s characters are, as Bakhtin pointed out, embodied thought or consciousnesseses. These foundational elements of Dostoevsky’s poetics resonate with Hegel’s philosophical view of Spirit as realisation of Thought as Self-Consciousness. Dostoevsky’s poetics of the unconscious represents in many ways an artistic cognate of Hegel’s conceptualisation of Spirit’s mediation between self-consciousness and the material world. Hegel’s ability to move with the Concept [Begriff] and progress through particular categories of Understanding [Verständnis] that otherwise result in fixities of thought and antinomies, together with his illuminating of transitions in the world-historical process (one reason why he’s so important today), find equivalents in both the form of Dostoevsky’s work, and the “characters” he puts on stage. These equivalents become clearer still, and arguably more relevant for us today, upon recognising the resonance of Hegel in contemporary law and society. Hegel’s intimate understanding of the human person that also animated Dostoevsky’s poetic universe permits us to know how we come to be what we are, why we do things as we do, as well as our ways of living together that are conducive to the freedom only we, the human kind, can express in the world. The need to grasp this knowledge seems as important now as it has ever been, and the literary output of Dostoevsky is but one path to greater self-awareness. On his stage, “characters” are always between things, as it were, the way they move through space (so often liminal, in doorways, on staircases) and, as Bakhtin has pointed out, among the stage props, which are symbolic rather than mimetic. A brief examination of the poetics of Dostoevsky’s novels will lead us to the broader contextual arc of Dostoevsky’s movement through and beyond the Westerniser/Slavophile antagonism of his day, which still animates the debates about the Russian Federation and its relation to Europe today, in the middle of Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Participant biographies

Dr Millicent Vladiv-Glover is Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, Chief Editor of The Dostoevsky Journal: A Comparative Literature Review, and President of the Australian Dostoevsky Society.

Richard Stewart LLB(Hons)(SCU), LLM(Melb) (Lawyer and PhD Law candidate, Southern Cross University)

What is personhood? the resonance of Hegel in Notes from the House of the Dead and more generally in contemporary Australian law and society

Nikolai Gladanac (BA Hon Monash, Vice-President (Research) Australian Dostoevsky Society)

What is personhood? On the Question of Freedom in Hegel and Dostoevsky.

Nicholas Ulbrick (PhD candidate, Swinburn U, Centre for Urban Transitions)

Led by Millicent Vladiv-Glover, with Olga Elena Ryygas, Elena Bystrova, Harry Buchanan, Lara Jakica, and Nicholas Ulbrick

Online

Monday July 25 2022, 2pm–4pm AWST.

This panel will try to explore the effects of the war in Ukraine on literature and culture—teaching, research, publishing. How do we approach the major writers of a nation which is committing crimes against humanity? How do we discriminate between art and life? Some of the panel participants are on the ground, near the war zone; some are in the Russian Federation, where the war cannot be mentioned; some have a life-long engagement with the European literary canon, of which Russian authors are an integral part; some are investigating the sociology of religious belief in Russia today; all are facing the problematic future of cultural communication and dissemination, which has suddenly become a clash of civilizations.

Amid Russia’s war on Ukraine, an urgent task is the preservation of our common heritage and shared cultural history, which is being thrashed out of existence in tandem with the devastation wreaked in Ukraine by the Russian forces. Cultural values must be disseminated: without dissemination culture dies. At the same time, dissemination must be ethical – without distortions of cultural documents and ideological appropriations, without myths replacing scientific interpretation of data.

Participant biographies

Dr Millicent Vladiv-Glover is Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, Chief Editor of The Dostoevsky Journal: A Comparative Literature Review, and President of the Australian Dostoevsky Society.

Olga Elena Ryygas is Adjunct Associate of the Sociology Institute at the Russian Academy of Sciences, and was a contributor to Echo of Moscow (Эхо Москвы).

Elena Bystrova teaches Russian Literature at Drohobych Ivan Franko State Pedagogical University.

Harry Buchanan is the author of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment: An Aesthetic Interpretation.

Dr Lara Jakica is the Secretary of Cross Cultural Community Connections, and holds a PhD in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies from Monash University.

Organisers:

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT DRESDEN, Zentrum Mittleres und Östliches Europa,

Institut für Slavistik

НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ ИССЛЕДОВАТЕЛЬСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ «ВЫСШАЯ ШКОЛА ЭКОНОМИКИ»

Международная лаборатория исследований русско-европейского интеллектуального диалога

Program – with participation of Australian Dostoevsky Society

State Institute for Art Studies (SIAS), Moscow, Russia

The Vladimir Vysotsky Research Centre for Russian Studies,

School of Humanities, Language and Global Studies, University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), Preston, UK

F.M. DOSTOEVSKY IN THE DIALOGUE OF CULTURES:

A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY

PROGRAMME

of this International Academic Conference

September 24-26, 2021

On the ZOOM platform

The working languages of the conference: Russian and English.

The time shown is of the Moscow (MSK) time-zone.

This is UTC/GMT+3 and BST+2.

Conference coordinators:

Liudmila Saraskina, Higher Doctor of Philology, Leading Researcher, State Institute for Art Studies

Ekaterina Salnikova, Higher Doctor of Cultural Studies, Head of Department of Artistic Problems of Mass Media, State Institute for Art Studies

Olga Tabachnikova, Doctor of Philosophy, Head of the Russian Section, Director of the Vladimir Vysotsky Centre for Russian Studies, School of Humanities, Language and Global Studies, University of Central Lancashire

Galima Lukina, Vice-Director of the State Institute for Art Studies, Higher Doctor of Arts, State Institute for Art Studies

Violetta Evallyo, Doctor of Cultural Studies, Senior Researcher, Executive Secretary of the scientific journal ‘Art & Culture Studies’

PROGRAMME

24 September

09.30–10.00

Opening of the conference on the ZOOM platform

Welcome addresses:

Natalia Sipovskaya

Higher Doctor of Arts, Director of the State Institute for Art Studies, SIAS, Moscow, Russia

Graham Baldwin

Professor, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Central Lancashire, UCLan, Preston, UK

10.00-14.00

Morning session

Chair: Liudmila Saraskina

10.00

Liudmila Saraskina

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Philology, Leading Researcher of Department of Artistic Problems of Mass Media, State Institute for Art Studies

“All Dostoevsky’s predictions have come true…”

The main results of the centenary (1821-1921)

10.20

Natalia Zhivolupova (†)

Russia, Nizhny Novgorod. Doctor of Philology, Professor, Nizhny Novgorod State Linguistic University named after N.A. Dobroliubov

Alexander Nikolaevich Kochetkov

Russia, Nizhny Novgorod. Doctor of Philology, Associate Professor, Nizhny Novgorod State Linguistic University named after N.A. Dobroliubov

Dostoevsky’s philosophy in the contemporary humanities

10.40

Arvydas Juozaitis

Lithuania, Klaipeda. Doctor of Philosophy, writer, playwright

“The Grand Inquisitor” and modern democracy

11.00

Stefano Aloe

Italy, Verona. Doctor of Philology, Professor of Slavic Studies, the University of Verona, Vice-President of the International Dostoevsky Society

Dostoevsky’s name in the Italian fascist discourse

11.20–11.40

Discussion

11.40–12.00

Coffee break

12.00

Svetlana Klimova

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, School of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, Faculty of Humanities, National Research University Higher School of Economics

“World Boundaries” in Dostoevsky’s and Wittgenstein’s oeuvre: What is Beyond?

12.20

Svetlana Korolyova

Russia, Nizhny Novgorod. Higher Doctor of Philology, Associate Professor, Head of the research laboratory ‘Fundamental and Applied Studies of Cultural Identity’, Nizhny Novgorod State Linguistic University named after N.A. Dobroliubov

Oscar Wild in a dialogue with Kropotkin and Dostoevsky: aesthetics as philosophy

12.40

Nikolai Podosokorsky

Russia, Velikii Novgorod. Doctor of Philology, Assistant Rector of the Yaroslav Mudryi Novgorod State University; First Deputy Editor-in-Chief of ‘Dostoevsky and World Culture. Philological journal’

The historical thinking of F.M. Dostoevsky: the Napoleonic theme in “The Diary of a Writer”

13.00

Anastasia Gacheva

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Philology, Leading Researcher at the Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of Department of Museum and Excursion Work of the Library No. 180 named after N.F. Fyodorov

F.M. Dostoevsky’s oeuvre in the context of themes and ideas of Russian cosmism

13.20–13.40

Discussion

13.40–14.40

Lunch

14.40–19.00

Afternoon session

Chair: Olga Tabachnikova

14.40

Olga Tabachnikova

Great Britain, Preston. Doctor of Philosophy, Associate Professor, Head of the Russian Section, Director of the Vladimir Vysotsky Centre for Russian Studies, School of Humanities, Language and Global Studies, University of Central Lancashire

“More black sorrow, poet”. Shestov and others as ideal readers of Dostoevsky

15.00

Elena Takho-Godi

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Philology, Professor, Department of Russian Literary History, Faculty of Philology, Moscow State University, Leading Researcher of the Department of Russian Literature of the late 19th – early 20th centuries, Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of Department for the Study of A.F. Losev’s Heritage of the Library ‘The House of A.F. Losev”, Editor-in-chief of the “Bulletin of the Library “The House of A.F. Losev””

“Dostoevsky vs Lev Tolstoy” in the eyes of Yu.I. Aikhenvald

15.20

Ilia Deikun

Russia, Moscow. 5th year student at the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute, a second-year MA student of literature at the Collège Universitaire Français (Moscow State University)

Anti-Dostoevsky. An attempt at demythologizing Dostoevsky’s philosophical “artistry” from the standpoint of logical analysis and sociology of literatures

15.40

Dmitry Bogach

Russia, Cheliabinsk. Doctor of Philology, Senior Researcher, Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “South-Ural State Humanities-Pedagogical University”

Hype about Dostoevsky: the monetization of the name.

The image of the writer in popular culture

16.00–16.20

Discussion

16.20–16.40

Coffee Break

16.40

Vladimir Viktorovich

Russia, Kolomna. Higher Doctor of Philology, Professor, State Social-Humanities University, Vice-President of the Russian Dostoevsky Society

Dostoevsky’s “Pushkin speech” and its interpreters

17.00

Liudmil Dimitrov

Bulgaria, Sofia. Higher Doctor of Philology, Professor, Department of Russian Literature, Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski

Another Russian troika. The case of Dostoevsky

17.20

Olga Chervinskaya

Ukraine, Chernivtsi. Higher Doctor of Philology, Professor, Head of Department of Foreign Literature, Literary Theory and Slavic Philology, Yurii Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University; Editor-in-chief of the scientific journal “Problems of Literary Criticism”

What is a “normal person”, according to Dostoevsky?

17.40

Liudmila Shchebneva

Moldova, Kishinev. Radio journalist, author, and presenter of the radio programmes “The Space of Culture” and “Russian House” of the National Radio of Moldova

Cultural and artistic figures of Moldova on Dostoevsky

18.00–18.20

Discussion

25 September

10.00–14.00

Morning Session

Chair: Ekaterina Salnikova

10.00

Tatiana Kasatkina

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Philology, Chief Researcher, Head of the Research Centre “F.M. Dostoevsky and World Culture”, Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Editor-in-chief of the “Dostoevsky and World Culture. Philological journal”

Dostoevsky: the author’s theory of creativity

10.20

Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover

Australia, Melbourne. Adjunct Associate Professor (Research) School of Languages, Literatures, Cultures and Linguistics, Monash University (Clayton Campus)

Dostoevsky’s doctrine of Beauty as a desire of the age

10.40

Ekaterina Salnikova

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Cultural Studies, Head of Department of Artistic Problems of Mass Media, State Institute for Art Studies

Psychology, physiology, and social environment

in Dostoevsky’s “The Possessed”

and in “The Moonstone” by Wilkie Collins

11.00–11.20

Discussion

11.20

David Chernichenko

Russia, Kazan. Student of the Kazan State Conservatoire

Madness as an epistemological problem in Dostoevsky’s “The Double”

11.40

Elena Chernichenko

Transnistria, Tiraspol. Senior Lecturer, Department of Russian and Foreign Literature, Transnistrian State University named after T.G. Shevchenko, member of MAPRYAL

Existential motives of Dostoevsky’s novels:

the phenomenon of a “positively beautiful person” in an alien world

12.00

Sergei Sharakov

Russia, Staraya Russa. Doctor of Philology, Leading Researcher at the House-Museum of F.M. Dostoevsky in Staraya Russa

The motive of beauty in Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot”

12.20–12.30

Discussion

12.30–12.40

Coffee Break

12.40

Yuri Bogomolov

Russia, Moscow. Doctor of Arts, Senior Researcher, Department of Artistic Problems of Mass Media, State Institute for Art Studies

Dostoevsky and Woody Allen on crime and punishment

13.00

Galina Tyurina

Russia, Moscow. Doctor of History, Head of Department for the study of the heritage of A.I. Solzhenitsyn, House of Russia Abroad named after A.I. Solzhenitsyn

Interpretations of crime and punishment by Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn

13.20

Anna Kumachyova

Great Britain, Lancaster. PhD Candidate in Film, Lancaster Institute for the Contemporary Arts

Dostoevsky and world cinema:

Screen adaptations of Dostoevsky’s Sonia Marmeladova

13.40

Cornelia Ichin

Serbia, Belgrade. Higher Doctor of Philology, Professor, literary critic, researcher of the Russian avant-garde, translator, Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade

Raskolnikov – a brother of the Yugoslav avant-gardists

14.00–14.20

Discussion

14.20–15.00

Lunch

15.00–19.00

Afternoon Session

Chair: Galima Lukina

15.00

Vladimir Kotelnikov

Saint Petersburg, Russia. Higher Doctor of Philology, Chief Researcher, Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House) RAS

Nastasia and Myshkin in Andrzej Wajda’s screen adaptation

15.20

Nikolay Khrenov

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Philosophy, Chief Researcher, Department of Artistic Problems of Mass Media, State Institute for Art Studies

A Russian version of the Superman: philosophical aspects of Dostoevsky’s “The Possessed” and of V. Khotinenko’s screen adaptation of the novel

15.40

Yulia Anokhina

Russia, Moscow. Doctor of Philology, Independent Researcher

Lizanka Khokhlakova, Nastasia Filippovna, ‘eternal Sonechka’: Dostoevsky’s female images in the creative biography of Margarita Terekhova

16.00

Yulia Mikheyeva

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Arts, Associate Professor, Sound Engineering Department, Russian State Institute of Cinematography named after S.A. Gerasimov

Sound spaces in “author” screen versions

of Dostoevsky’s ‘A Gentle Creature’

16.20

Violetta Evallyo

Doctor of Cultural Studies, Senior Researcher, Executive Secretary of the scientific journal “Art & Culture Studies”

“A Raw Youth”: the image of the city in the novel by F.M. Dostoevsky

and in the screen adaptation by E.I. Tashkova

16.40-16.50

Discussion

16.50–17.00

Coffee Break

17.00

Tatiana Boborykina

Saint Petersburg, Russia. Doctor of Philology, Associate Professor, Senior Lecturer, Department of Interdisciplinary Research in Literature and Language, St. Petersburg State University

Dostoevsky on the ballet stage. The dancing Karamazovs

17.20

Galima Lukina

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Arts, Deputy Director for Research, State Institute for Art Studies

F.M. Dostoevsky and S.I. Taneyev: resonances and overlaps

17.40

Igor Kondakov

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Department of History and Cultural Theory, Faculty of Cultural Studies, Russian State University for the Humanities, and Leading Researcher, Department of Artistic Problems of Mass Media, State Institute for Art Studies

“The Gambler”: an opera by Sergei Prokofiev

18.00

Elena Artamonova

Great Britain, Preston. PhD, Violist and Researcher, Lecturer in Russian, School of Humanities, Language and Global Studies, University of Central Lancashire

“Christmas Tree”: an opera by Vladimir Rebikov.

Reception of the composer and his work in Britain

(based on materials of the English-language press)

18.40–19.00

Discussion

26 September

10.00–14.00

Morning Session

Chair: Violetta Evallyo

10.00

Nadezhda Mikhnovets

Russia, Saint Petersburg. Professor, Higher Doctor of Philology, Department of Russian Literature, Russian State Pedagogical University named after A.I. Herzen

Dostoevsky on the specifics of theatrical and dramatic art

10.20

Zinaida Gafurova

Russia, Moscow. Head of the Literary and Drama Section of the Moscow Drama Theatre “Soprichastnost”

Alexandra Frolova

Russia, Moscow. Doctor of History, Senior Researcher, Department of the Russian People, Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Russian Academy of Sciences

“Dostoevsky-Quartet” on stage:

the play “Foma Fomich creates universal happiness…”

in the theatre “Soprichastnost”

10.40

Ekaterina Timchenko

Russia, Sevastopol. 4th year student of the Faculty of History and Philology (Department of Russian Language and Literature), Sevastopol Branch of the Moscow State University named after M.V. Lomonosov

An interpretation of the image of Stavrogin

in the play by G.A. Lifanov ““The Possessed”. Shards of false ideas”

on the stage of A.V. Lunacharsky Theatre in Sevastopol

11.00

Tatiana Magaril-Iliaeva

Russia, Moscow. Researcher at the Research Centre “F.M. Dostoevsky and World Culture”, Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Deputy-Editor of the “Dostoevsky and World Culture. Philological journa”

“The Dream of a Ridiculous Man” in contemporary theatre performances

11.20–11.40

Discussion

11.40–12.00

Coffee Break

12.00

Konstantin Barsht

Russia, Saint Petersburg. Higher Doctor of Philology, Professor, Leading Researcher, Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House) RAS

On new findings in the studies of drawings by F.M. Dostoevsky

12.20

Pavel Fokin

Russia, Moscow. Doctor of Philology, Head of Department of the State Literary Museum ‘Museum-apartment of F.M. Dostoevsky’, Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House) RAS

Mikhail Shemyakin’s reading of Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment”

12.40

Elena Kudryavtseva

Russia, Saint Petersburg. PhD student, Faculty of Philology, Department of Russian Literature, Russian State Pedagogical University named after A.I. Herzen

The ekphrasis of “The Holy Family”

in Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground”

13.00–13.20

Taisia Frolova

Russia, Moscow. Student at the Literary Institute. A.M. Gorky

The ekphrasis of the painting “The Sistine Madonna”

in Dostoevsky’s “The Possessed”

13.20–13.40

Discussion

13.40–14.00

Lunch

Afternoon Session

Chair: Liudmila Saraskina

14.00

Natalia Krivulya

Russia, Moscow. Higher Doctor of Arts, Professor of the Moscow State University named after M.V. Lomonosov, professor at the Higher School of television, Head of Department

Visual metaphor as the basis of animation interpretations

of Dostoevsky’s oeuvre

14.20

Vera Biron

Russia, Saint Petersburg. Deputy Director for creative projects of the St. Petersburg Literary Memorial Museum of F. M. Dostoevsky

“Dostoevsky the character” in the graphics of Igor Kniazev

and in museum projects

14.40

Ekaterina Chernetskaya

Russia Moscow. Acting Head of the Funds Storage Department, Curator of Graphics of the State Museum and Exhibition Centre ‘ROSIZO’

Dostoevsky’s influence on the work of the Belgorod artist S.S. Kosenkov

(a case study of the ROSIZO collection)

15.00

Maria Radchenko

Russia, Sevastopol. Doctor of Philology, Associate Professor, Faculty of History and Philology (Department of Russian Language and Literature), Sevastopol Branch of the Moscow State University named after M.V. Lomonosov

Dostoevsky’s “A Nasty Story” in the graphic and literary interpretations

by Yu.P. Annenkov

15.20

Tatiana Yuriyeva

Russia, Saint Petersburg. Higher Doctor of Arts, Professor, St. Petersburg State University, Honoured Art Worker of the Russian Federation, Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art named after S.P. Diaghilev (St. Petersburg State University)

Graphic interpretations of the works of F.M. Dostoevsky

in Russian and Western culture of the 20th century

15.40–15.50

Discussion

15.50–16.00

Coffee Break

16.00

Elena Akelkina

Russia, Omsk. Higher Doctor of Philology, Professor, Director of the Omsk Regional Centre for the Study of Dostoevsky’s oeuvre, Omsk State University named after F.M. Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s experience in the work and life of M.V. Nesterov

16.20

Yulia Petrova

Russia, Omsk. Senior assistant, Omsk Regional Centre for the Study of Dostoevsky’s oeuvre, Omsk State University named after F.M. Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s Siberian images in the paintings and graphics

of the Omsk artist G.P. Kichigin

16.40–17.00

Discussion

17.00

Natalia Ashimbayeva

Russia, Saint Petersburg. Doctor of Philology, Director of the St. Petersburg Literary-Memorial Dostoevsky Museum

New literary exposition in the St. Petersburg Dostoevsky Museum.

Its creative principles; Content; Image

17.20

Albina Bessonova

Russia, Kolomna. Doctor of Philology, Leading Researcher of the State Social-Humanities University, Director of ‘The Cultural and Educational, Scientific Restoration and Museum Centre “Zapovednoye Darovoye”’

‘Darovoye’ yesterday, today, and tomorrow

17.40–18.40

Round Table

(participants: museum staff and researchers)

New expositions of Russia’s Dostoevsky museums and the “genius of place”

Moderator: Natalia Ashimbayeva

Director of the St. Petersburg Literary-Memorial Dostoevsky Museum

18.40

Concluding remarks

КОНЦЕПЦИЯ КРАСОТЫ ДОСТОЕВСКОГО КАК ЖЕЛАНИЕ ЭПОХИ

Слободанка Владив-Гловер

Университет Монаш, Австралия

(перевод: Др Наталия Батова, Мельбурн)

Достоевский выработал собственное «учение о красоте» почти сразу по возвращении на русскую литературную сцену, после того как он был осуждён как политический заключённый и провёл десять лет в сибирской ссылке. В статье, появившейся в 1861 году в журнале «Время», который на тот момент Достоевский только начал издавать вместе со своим младшим братом Михаилом, писатель ведёт полемику со своим современником, видным «радикальным» критиком Николаем Добролюбовым, по «вопросу искусства»1. Одной из причин полемики стала повесть «Маша» украинской писательницы М.А. Маркович (1834–1907), писавшей под псевдонимом Марко Вовчок. Добролюбов положительно оценил прозаические произведения Марка Вовчка в своей статье под названием «Черты для характеристики русского простонародья», опубликованной в прогрессивном журнале «Современник»2. Достоевский обвинил Добролюбова, прогрессивная эстетика которого в целом не противоречила его, Достоевского, собственной, в одобрении художественно неполноценного литературного произведения в силу его пользы для общества, но за счёт настоящего искусства, которое, по Достоевскому, может быть намного полезнее для современников, даже если оно «антологично», то есть если оно создано по европейскому канону прошлых веков. В статье Достоевского, которая вместо развития аргумента в некой логической прогрессии представляет собой и по структуре, и по стилю довольно сложное эссе, особый интерес вызывает своеобразное использование понятия «почва» по отношению к автономности и уникальности исторически обоснованного эстетического произведения.

Первое упоминание о «почве» встречается в следующем отрывке, в котором Достоевский отмечает, что обращению Марка Вовчка с вымышленными персонажами не хватает «основательности» и «правдоподобия»:

Скажите: читали ли вы когда-нибудь что-нибудь более неправдоподобное, более уродливое, более бестолковое, как этот рассказ? Что это за люди? Люди ли это, наконец? Где это происходит: в Швеции, в Индии, на Сандвичевых островах, в Шотландии, на Луне? Говорят и действуют сначала как будто в России; героиня – крестьянская девушка; есть тетка, есть барыня, есть брат Федя. Но что это такое? Эта героиня, эта Маша, – ведь это какой-то Христофор Колумб, которому не дают открыть Америку. Вся почва, вся действительность выхвачена у вас из-под ног. Нелюбовь к крепостному состоянию, конечно, может развиться в крестьянской девушке, да разве так она проявится? Ведь это какая-то балаганная героиня, какая-то книжная, кабинетная строка, а не женщина? Всё это до того искусственно, до того подсочинено, до того манерно, что в иных местах (особенно, когда Маша бросается к брату и кричит: «Откупи меня!») мы, например, не могли удержаться от самого веселого хохота3.

Достоевский подчеркивает, что если писатель не может выразить что-то «в русском духе», с помощью «русских персонажей», значит, такого «факта» русской жизни не существует. Этот «русский дух» не следует рассматривать в мистическом смысле, как в выражении «русская душа», но как историческую правду или историческое обоснование национального сознания, формирующего социальные явления. «Дух» здесь имеет то же значение, что и в 19 веке, то же, что означает «Geist» в немецком языке, – всеобъемлющее выражение самосознания личности или народа. В знаковой «Феноменологии духа» (Die Phänomenologie des Geistes) Гегеля предлагается толкование этого русского понятия. Достоевский повторяет своё обвинение в том, что «почва» выхвачена из-под ног столь манерным представлением русской жизни на примере персонажей Марка Вовчка, потому что такому представлению не хватает выразительных средств и «художественности», которые могли бы «убедить» читателя в «правдивости» подобного представления. Достоевский потенциально ставит ту же цель для искусства, что и Толстой: оно должно быть аутентичным (соответствовать историческому моменту) и заразительным (убедительным).

Понятие о художественности как о выразительном средстве, которое должно быть в арсенале хорошего писателя, по мнению Достоевского, является основным мотивом и ведущим понятием во взгляде Достоевского на искусство, представленном в продолжение статьи. Художественность связана с образом красоты, «созданным» «художественным творчеством»; Красота становится «кумиром», принимаемым безоговорочно и повсеместно, поскольку человек желает Красоты («жаждет её») и не может жить без неё. Человек особенно нуждается в Красоте в период борьбы и отчуждения от его/её реальности. Красота – это «гармония и спокойствие»; Красота присуща «всему здоровому, то есть наиболее живущему» и «есть необходимая потребность организма человеческого»4. Красота, таким образом, является нормой, но нормой ненормативной. В таком абстрактном смысле Красота этична.

Данная диалектика искусства и человеческого бытия приобретает дополнительное измерение в свете воззрения Достоевского на историю, которое подробно рассматривается в следующем разделе его статьи. «Мы не можем знать нормальных, естественных путей полезного», потому что «история не является точной наукой», даже если перед нами все «факты». Достоевский спрашивает: как мы можем определить чётко и неопровержимо, «что надо делать», чтобы достичь идеала и того, к чему стремится всё человечество? Он отвечает: мы можем угадывать, изобретать, предполагать, изучать, мечтать и рассчитывать, но невозможно рассчитать каждый будущий шаг всего человечества, вроде календаря. Мы строим системы, выводим следствия, но мы не можем даже близко измерить, насколько полезна была «Илиада» для человечества и для наших современников. Эффект, который такое великое произведение искусства оказывает на читателя заключается в том, что оно заставляет «душу» смотрящего (читателя, получателя) «трепетать» перед ним. Тот факт, что произведение искусства может вызывать «трепет», приводит нас в область классической эстетики Лонгина I века нашей эры и обращает нас к его трактату «О Возвышенном»5. «Трепет» как реакция души встречается и в размышлениях Канта о Возвышенном. Фактически, изложенная ранее мысль Достоевского о том, что Красота принимается «безоговорочно», имеет похожий оттенок: «… человек принимает красоту просто потому, что Красота есть Красота, и с благоговением преклоняется перед нею»6. «Благоговение» («чувство почтительного уважения, смешанное со страхом или удивлением») и «уважение» – это именно те выражения, которые Кант использует в описании отношения человека к Возвышенному.7 Вывод, который можно сделать из определения Достоевским произведения искусства, пронизанного эстетикой классицизма и эстетикой эпохиПросвещения, заключается в том, что произведение искусства – это новое Возвышенное современной эпохи.

Красота и, предположительно, произведение искусства, её отражающее, также связаны с историей. Красота и её «вечные идеалы» (напоминающие «вечную красоту» Бодлера) есть «часть всемирной истории», как говорит Достоевский. При этом он добавляет, что «возможно взглянуть на жизнь прошлого и идеалы прошлого не наивно, а исторически. «При отыскании красоты человек жил и мучился. Если мы поймем его прошедший идеал и то, чего этот идеал ему стоил, то, во-первых, мы выкажем чрезвычайное уважение ко всему человечеству, облагородим себя сочувствием к нему, поймем, что это сочувствие (…) гарантирует нам же, в нас же присутствие гуманности, жизненной силы и способность прогресса и развития»8. Помимо такого «исторического» отношения к прошлому, можно также относиться к нему, по Достоевскому, «байронически». Можно чувствовать себя истощённым, испытывая противоречивые чувства отчаяния, тоски, безотчетного позыва, колебания, сомнения и в то же время умиления «перед прошедшими, могущественно и величаво законченными судьбами исчезнувшего человечества». В этом «байроническом энтузиазме» перед «идеалами Красоты», созданными прошлым и оставленными нам в «вековечное наследство», мы «изливаем всю тоску о настоящем», вызванную не бессилием, а «пламенной жаждой жизни и от тоски по идеалу», который мы приобретаем через страдание.9Два взгляда Достоевского на «Красоту» – с одной стороны, Красота с ее «вечными идеалами», а с другой – «байроническое отношение» к Красоте прошлых веков и завершённых человеческих судеб, оба фактически подпадающие под понятие ‘исторического’ взгляда на красоту, – во многом соответствуют двум ‘историческим’ выражениям Красоты Бодлера – Красоте «вечной» и Красоте «относительной». В то время как Бодлер считает, что «вечную красоту» трудно уловить и определить, Достоевский пытается определить Красоту с точки зрения Кантовского Возвышенного и с точки зрения (будущей) психологии искусства10 как «человеческую потребность» и как элемент, преобразующий человеческое существование. Достоевский цитирует стихотворение Афанасия Фета «Диана» как пример «воплощения» этого (Байронического) «энтузиазма» к прошедшей Красоте: богиня «не воскресает», она в вечности, но созерцание её красоты (переданное Фетом как поэтическое видение) воскрешает прошлое двухтысячелетней давности в «душе поэта», который передаёт это прошлое как живую силу со всей страстью к жизни своим современникам. Желание и энтузиазм к прошлому таит в себе «бесконечное будущее»; «вечное искание» человека в этом будущем называется «жизнию». «Какая тоска о настоящем» скрывается «в этом энтузиазме к прошедшему», – восклицает Достоевский.11Далее Достоевский вводит понятие «универсального человечества», которое определяет его полемику против утилитарного искусства и подводит читателя к провозглашению его художественного кредо. Спорный вопрос, который возникает между строк и со ссылкой на критику Добролюбовым «антологической» литературы европейского Классического прошлого, заключается в том, является ли эта литература европейского классического наследия («Илиада», Данте, Шекспир и классическая поэзия о богах и богинях, подобная той, которая вдохновила Фета на «Диану») «полезной» в нынешних социальных условиях русской национальной жизни. Возражение Достоевского состоит в том, что русский народ после Петровских реформ продемонстрировал замечательную способность «отвечать» на «общечеловеческое» и на «литературные произведения европейских народов», которые были «почти нашими»:… мы связаны и исторической и внутренней духовной нашей жизнью и с историческим прошедшим и с общечеловечностью. (…) литературы европейских народов были нам почти родные, почти наши собственные, отразились в русской жизни вполне, как у себя дома.12Если не учитывать привилегированный доступ русских к «общечеловеческому», – мысль, которая несколько преувеличена, но при этом регулярно обсуждается в комментариях и привязывается к идее «русского мессианства», приписываемого Достоевскому, – можно рассматривать высказывание Достоевского как пылкое заявление в пользу тезиса о том, что «Россия есть Европа» и что «европейская культура принадлежит России». Достоевский приводит творчество Пушкина в качестве отличного примера так называемого присвоения русскими европейской культуры и перенесения её на русскую «почву» и считает это событие подвигом творческого гения, превратившим Пушкина в «величайшего национального поэта», который есть «полнейшее выражение направления, инстинктов и потребностей русского духа в данный исторический момент». Таким образом, Пушкин – это «современный тип всего русского человека» в его «историческом стремлении» (а именно, в его восприятии истории) и в его «общечеловеческом стремлении» (а именно, в его стремлении быть частью европейской культуры во всех её аспектах (художественных, а также политических, о которых Достоевский не мог говорить вслух). Пушкин своим искусством олицетворяет настоящий «исторический момент» в русской национальной жизни. Хотя Пушкин и не касался «социальных тем» современной «утилитарной» литературы, его творчество для Достоевского – это идеальный ответ потребностям современной русской жизни, – такой вывод можно сделать из этой литературной «полемики» со скрытым политическим посылом. Несмотря на то, что Достоевский не затрагивает тему ссылки Пушкина, чтобы не вызывать ассоциацию с Декабристами или с «республиканством» Пушкина, его скрытый смысл, должно быть, стал понятен всем его читателям, но, к счастью для него, остался скрытым для цензуры.Художественное кредо Достоевского вынуждает его безоговорочно следовать целям поэтики Реалистов, которые находят свое выражение в теории и на практике в произведениях «Les français», «Наши» и «Портреты англичан». Поскольку Достоевский убеждён, что искусство и красота «всегда современны», он может поднять выражение Красоты в его романах на ступеньку выше в метафорическом и метафизическом смысле и остаться верным историческому моменту и задаче отображения эпохи для потомков. Хотя Достоевский не создаёт социальные «типы» или «характеры» в стиле физиологов Натуральной Школы или в стиле описания нравов в «Наших», он делает зарисовки «исторического бессознательного» его эпохи, что делает его «историком» своего времени в духе Реалистов. Как историк-генеалог, Достоевский опирается на эвристическое качество художественности, которое он преподносит в своем учении о Красоте как путь к познанию его эпохи.

Примечания

Cambridge: Hackett, 1987).

10. Выготский определяет Красоту как «человеческую необходимость», которая, в частности, проявляется в соотношении с тяжелой работой, когда искусство (в частности, музыка) приносит облегчение от работы благодаря своей ритмичности. Это определение почти перекликается с утверждениями Достоевского о том, что искусство «полезно», особенно во время кризиса в делах человека или человечества. Понимание Достоевским термина «трепет» (впервые упомянутого Лонгиным) как аффективное воздействие произведения искусства в контексте его собственного анализа Красоты как нового Возвышенного также используется Львом С. Выготским в его «Психологии искусства». (Москва: Лабиринт, 2010), с. 255. Выготский также обсуждает «заразность» как влияние произведения искусства со ссылкой на Толстого «Что такое искусство?», отвергая тезис Толстого о том, что возбуждающее воздействие лучше всего проявляется в военной и танцевальной музыке, а не в других видах искусства. Лев С. Выготский, Психология искусства, с. 257. Джозеф Франк интерпретирует «скрытую внутреннюю ностальгию» по красоте в эссе Достоевского как «тоску по новой теогонии», которая является «тоской по рождению Христа, по Богочеловеку, который должен был … вытеснить неподвижную и далёкую римскую богиню». То, что Достоевский делает со статуей Дианы у Фета, направлено на то, чтобы показать, что это не материя (камень, мрамор), это бог. Другими словами, художника обладает силой превращать материю в дух. Во всей статье Достоевского Христос или православие не упоминаются ни в прямом, ни в переносном смысле. Внимательное прочтение текста Достоевского не лежит в основе интерпретации Франка. См: Joseph Frank, Dostoevsky: The Stir of Liberation 1860-1865. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP, 1986, p. 84.

See the blog from Brill where this interview originally appeared.

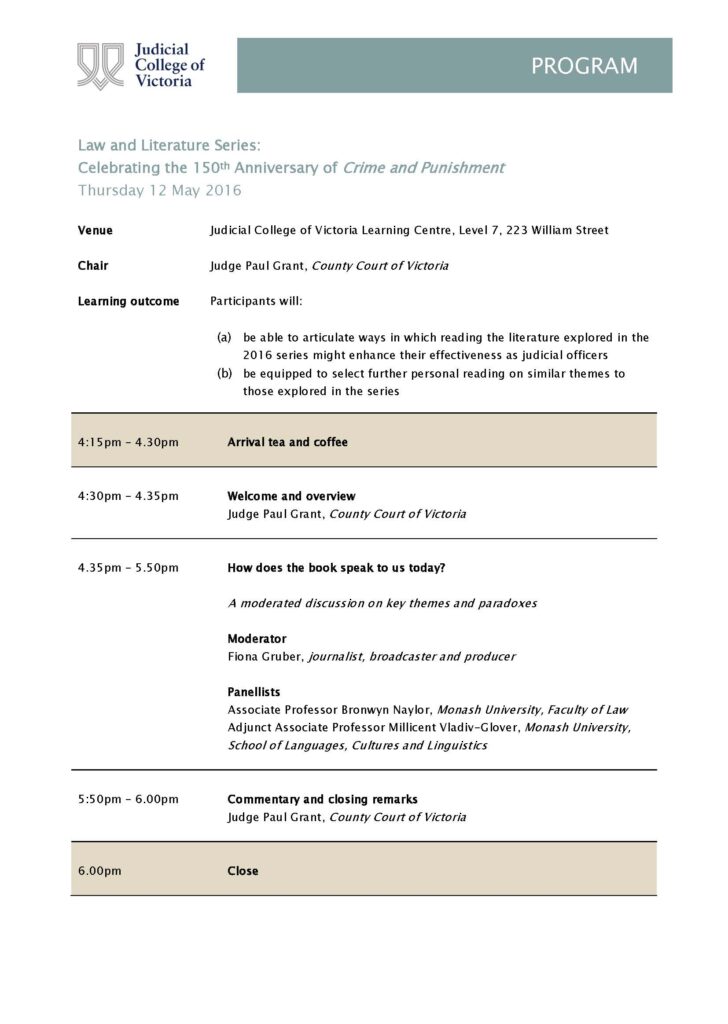

Held in 2016 as part of the Law and Literature series at the Judicial College of Victoria Learning Centre.

WORKING NOTES – Millicent Vladiv-Glover

I want to pick up on three points made by Fiona:

James Joyce’s judgement of the impact of Dostoevsky’s aesthetics (artistic form) on European Modernism ( “postmodernism” and beyond)

James Joyce’s jocular exchange with his son is reported by Samuel Beckett and quoted by Joyce’s biographer, Ellmann[1], in which Joyce is alleged to have said that C&P was “a queer title for a book which contained neither crime nor punishment.”

It is true that the “murders”, although premeditated, are represented as “symbolic”, not “mimetic violence” (Rene Girard [December 25, 1923 – November 4, 2015] Violence and the Sacred [1972]). Although they “take place” in scenic, staged, graphic form in the text, they are a kind of part of R’s “inner experience” (of which more below).

.

The reception of C&P in 1866 by the Russian reading public and what some critics thought the novel was about.

[“Glasny sud”, 1867, 16, (28)]:

Начало этого романа наделало много шуму, в особенности в провинции…заинтересовала всех не литературная сторона романа, а, так сказать, тенденциозная…о новом романе говорили даже шепотом, как о чем-то таком, о чем вслух говорить не следует…С этого времени научное слово ‘анализ’ получило право гражданства…

[“The beginning of this novel created a great stir, especially in the provinces…everyone’s interest was aroused not by the literary dimension of the novel, but of its, so to speak, tendentious one…people talked about the new novel in whispers, as if speaking aloud about it was something not done…From that time one, the scientific word ‘analysis’ acquired citizenship status…”] (Trans. MV-G)

[С. Капустин, “По поводу романа Преступление и наказание,” Женский вестник, 1867, No 5]:

Роман этот возбуждает в обществе толки самые разнообразные. Приводим некоторые…: «Что можно сказать особенного на эту избитую тему?» говорят люди, начитавшиеся вдоволь судебно-уголовных процессов и романов на подобны темы. «Как жалко этого молодого человека (преступника) – он такой образованный, добрый и любящий, и вдруг решился сделать такой ужасный поступок,» отзываются люди,…читающие всякого рода романы и не размышляя о том, для чего они пишутся. «Фу, какое скверное и мучительное впечатление остается после этой книги!…» говорят, бросая ее, люди, доказывающие этими самыми словами, чти ни одно слово романа не оставлено ими без внимания, и что мысли, возбужденные им, тяжело западают в голову, несмотря на все желание от них отделаться.»

[S. Kapustin, “About the novel Crime and Punishment,” Feminine Messenger, 1867, No. 5]

This novel has given rise to many different interpretations in (our) society. We shall cite some of them: “What can one say that is special on this hackneyed subject?” , say the people who have read to excess the legal criminal trials and novels on similar themes. “How sorry one feels for that young man (the criminal) – he is so well educated, good of heart and loving, and then he suddenly decides to commit such a terrible act,” say the people who read all sorts of novels without contemplating for what purpose such novels are written. “Ugh, what a depressing and nauseating feeling lingers after reading this book!…say the people who fling the book away, not realizing that with these very words they prove that not a single word of the novel passed unnoticed for them, and that the thoughts aroused by the novel, have sunk deep into their minds, notwithstanding their desire to be rid of them.” (Trans. MV-G)

Nikolai Strakhov wrote that the effect of the novel on the “general reading public”, was “spectacular”. “All that was being read in that year 1866 was Crime and Punishment, all that lovers of reading talked about was that novel, about which they complained because of its crushing power, and because of the depressing feeling it left them with, so that people with strong nerves almost became ill, while people with weak nerves had to leave off reading.” [F M Dostoevskii, PSS v 30 tt., Tom 7: 349 (Trans. MV-G)

Dostoevsky wrote to his niece, S. A. Ivanova (8/20 March 1869) that his publisher, Katkov, had told him that because of the serialization of C&P, “Russian Messenger” acquired “500 additional subscribers.” (ibid., 349).

Dostoevsky left to posterity a conspectus of the novel, in which he gave a brief exposition of his conception. This is contained in the famous draft (which was sent) of D’s letter to Katkov, to whom he was offering his future work:

“It is a psychological account of a crime. The action is contemporary. It is set in the present year. A young man, an expelled university student, petit bourgeois in origin, is living in extreme poverty. Through the shallowness and instability of his thought he has surrendered himself to certain strange and half-baked ideas which are in the air, and has decided to extricate himself at one stroke from his terrible position.” (quoted in: Richard Peace, Dostoevsky: An Examination of the Major Novels, Cambridge UP, 1971, p. 25)

This letter has given rise to a whole exegetical tradition in Dostoevsky scholarship, which takes the view that Raskolnikov’s ideas are discredited by Dostoevsky in the novel. It has also led, indirectly, to a Christian framing of the novel’s content.

What this and other negative interpretations of Raskolnikov’s radicalism ignore is that the author’s exegesis about his future novel was a sales pitch to a publisher who had to contend with the censorship conditions of Tsarist Russia of the 1860s. The “new people” of the 1860s were coming into public view, culminating in the rise of crimes which resembled Raskolnikov’s. The “protest” against the social inequalities was taking political shape: to wit, Karakozov’s attempt on the Tsar, Alexander II, in April 1866, while C&P was still being written. Dostoevsky himself was a political ex-con. Do you think that he was going to make an ex cathedra statement about his politics and place this in the public arena?

This brings us to the hermeneutic analysis of Dostoevsky’s poetics, which offers a key to the revolutionary nature of his novel, revolutionary not only in the political sense but hand in hand with his politics, on the plane of aesthetics and ethics.

FMD as a “psychologist”

Is the novel just a psychological account of a crime, with elements of the horror, which the camera’s eye of the text follows in the same way as the camera in a snuff-movie? Is this why we are still reading the novel?

Although this technique of recording factual, concrete detail creates tension, the graphic scene of the murder for example is just one in a series of the text camera’s “witnessing” of R’s self-crucifixion. What follows, but also precedes, the double murder, is a tortuous journey through the arid landscape of R’s unconscious, which is represented as if he could have formulated this “inner experience” in the words of the text.

MAGRITTE PICTURE of LOST JOCKEY

The text (or its Fictional Narrator) reconstructs the thought of the character from the character’s point of view.

That is why the reader feels R.’s pain as if it were the reader’s own. The empathy with R. as it were ‘castrates’ the reader: it is this violence of the text, which constitutes the only ‘real’ violence in/of the novel. It is as if the reader were walking through the eerie landscape of alienation – the division of the Self into Oneself and an Other – as a double of R.

All MODERNIST texts appropriate this technique without anyone having surpassed FMD!

What is at stake in alienation is the formation of an individual subject, called a subject of language in psychoanalytic theory. However, FMD does not approach alienation through psychoanalysis (even though Freud and Nietzsche both said they learnt from him); he approaches it via an ANALYTIC of REASON: themes of reason/mind/cogito/being out of one’s mind (Ум/разум/не в своем уме).

It is the POWER – WILL – REASON triad, which crops up repeatedly in the narrative. It is not always felicitously rendered by the translator (David McDuff, Penguin 1991):

‘That’s enough!’ he said, solemnly and decisively. ‘Begone, mirages, begone, affected terrors, begone, apparitions!…There’s a life to be lived! (…) My life didn’t die along with the old woman! May she attain the heavenly kingdom – enough, old lady, it’s time you retired! Now is the kingdom of reason and light, and freedom…and strength…and now we shall see! Now we shall measure swords!’ he added, self-conceitedly, as though addressing some dark power and challenging it. (…)

‘Strength, strength is what I need: one can’t get anything without strength; and strength has to be acquired by means of strength – that’s what they don’t understand, he added with pride and self-assurance and continued his way across to the other side of the bridge, hardly able to shift his legs. (Penguin, 236)

«Довольно! – произнес он решительно и торжественно, прочь миражи, прочь напускные страхи, прочь привидения!.. Есть жизнь! Разве я сейчас не жил? Не умерла еще моя жизнь вместе с старою старухой! Царство ей небесное…Царство рассудка и света теперь и…и воли, и силы…и посмотрим теперь! Померяемся теперь! Прибавил он заносчиво, как бы обращаясь к какой-то темной силе и вызывая ее. – (…) Сила, сила нужна: без силы ничего не возьмешь; а силу надо добивать силой же, вот этого-то они и не знают,» прибавил он гордо и самоуверенно и пошел, едва переводя ноги, с моста.» (Том 5, Собр.Соч.. в 10.ти тт, 1957, «Худ. Лит», стр. 197)

The question of whether it is right to kill for a cause is never resolved by Raskolnikov or the novel itself. The novel provides a model for the revolutionary (and ideological terrorist) of all times!

What is the issue is Raskolnikov’s individual Categorical Imperative (CI), grounded in his own unconscious, which itself touches on the unspeakable, the unrepresentable, the uncanny. (Old woman in his dream laughing at him trying to kill her). This CI is not the Law of the Christian God, nor is it the Kantian CI of the maxims: «I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become universal law.» (The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, 4:402)

Raskolnikov’s CI is that of the modern split subject of language, whose Ego is at the mercy of the Id and of the drives – the sex drive and the death drive. The entire novel is the story of this struggle, NOT of the rational vs the irrational, not of one kind of morality pitted against another, but of the individual who is subject to the drives of his unconscious, the life drives and the death drives. Raskolnikov oscillates between them. The rest is metaphor. And a love story!

The novel is above all about love and sensibility and the expressivity of emotions and affects, about symptoms (KI is a SYMPTOM), about sado-masohism and about sacrife and transgression.

There are two kinds of sacrife, both involve transgression:

to sacrifice oneself for others and to sacrifie others for a cause.

Sonia’s sacrifice can be subsumed under Kant’s CI of the maxims.

Other «new people» in the novel, who conform to this poetics of the split subject, are KI, Dunia, Marmeladov. The sociological types of the «new people» are parodied by FMD (the phalansteries, the open marriages).

The will to power is established as the ground of personality: Katerina Ivanovna (KI) is all will (394/Vol /R); Dunia is said to be a spitting image of her brother – strong will and pride (249/Vol 5/R); minor character, Luzhin, does not give up his “idea” (of defeating R. by drawing Sonia into the intrigue with the allegedly stolen 100 rouble note)(421/Vol 5/R)

[1] In Conversations with James Joyce, Arthur Power tells us that Joyce praised Dostoevsky as being “the man more than any other who has created modern prose, and intensified it to its present-day pitch.” He also attributes to Joyce the statement that Dostoevsky “was always enamoured of violence, which makes him so modern” (Power, 58, 59). Yet the wording of both statements is so unlike Joyce, who was much more apt to make fun of such pretentious pronouncements than to make them, that one tends not to trust Power’s memory altogether. I am more inclined to believe Samuel Beckett’s account of Joyce’s dispute with his son on the value of Doseoevsky: “Giorgio liked to display in argument an obstinacy of the same weave as his father’s, informing him for example that the greatest novelist was Dostoevski, the greatest novel Crime and Punishment. His father said only that it was a queer title for a book which contained neither crime nor punishment” (quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, 485). Source:

Galya Diment,Tolstoy or Dostoevsky and the Modernists

sites.utoronto.ca/…/pages%2076-81%20conference%20paper%20volum…