HISTORY

DOSTOEVSKY IN AUSTRALIA

- Dostoevsky in Australia

- Selected Bibliography

- Dmitry Vladimirovich Grishin

- CV Dmitry Vladimirovich GRISHIN

Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover [1]

DOSTOEVSKY IN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY AND MISSION

Russian Studies and the Christesen Years at the University of Melbourne

Australian Dostoevsky studies appeared almost simultaneously with the establishment of Russian studies, introduced to Australian universities by the Russian pre- and post-World War Two Russian emigres. The founder of Russian language and literature as a university discipline in Australia was Nina Mikhailovna Christesen (MA). She arrived in Brisbane from Harbin in Manchuria as a sixteen-year-old girl. In Harbin, the Russian intelligentsia who fled before the Russian Revolution in 1917-1918, established their own cultural and educational intuitions, in which Nina Mikhailovna received her education so that when she arrived in Australia, Mrs Christesen was a fully-fledged Russian culture carrier, with a strong sense of cultural identity. With her husband, Clem Christesen, she also became a part of the Australian progressive intelligentsia, who, paradoxically, was sympathetic to Soviet Russia of the Cold War. Nina Mihkailovna straddled the political divide between her traditional Russia of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and the new Soviet Russia of Marxism-Leninism with elegance and tact: with her husband Clem, she received many Soviet visitors at their “dacha” in Eltham, which was also the site of many Russian Department Easter Camps, in which Nina Mihkailovna presided with old Russian Easter customs, serving “paskha”, “kulich” and “piroshki”, while speaking only Russian with all of her students. These students began to materialise from 1949 onwards, when Mrs Christesen began teaching Russian courses at the University of Melbourne, supported by a small collective of mainly but not only Russian scholars who had come to Australia at various times and from various countries. They were migrants in the post-World War Two wave of displaced persons or those who had been abroad, in the UK, during the war, like Reginald De Bray and Boris Christa. Both De Bray[1] and Christa were later appointed to newly established chairs of Russian at Monash University and the University of Queensland, respectively. Another arrival was Zinaida Andreevna Uglitskaya, who studied linguistics under V.V. Vinogradov, and who gave the new Department of Russian gravitas in the teaching of the Russian language according to the Academy Grammar. In 1953, Dmitry Vladimirovich Grishin joined the teaching staff of the Department of Russian Language and Literature; he came to Australia from Germany in 1949, after graduating at Moscow State University with a kandidat nauk degree.

Dostoevsky Studies and the Grishin Years at the University of Melbourne

Dmitry Grishin introduced the study of Dostoevsky as a research field with his own research into Dostoevsky’s life and works, which became one of the first doctoral dissertations on Dostoevsky in Australia (PhD Melb 1957); it was later published as a book entitled Dostoevsky’s Diary of a Writer (1966). Grishin immediately set about teaching Dostoevsky to undergraduates enrolled in the Faculty of Arts for a Bachelor’s degree and soon he also had postgraduates working on Dostoevsky. A new university discipline, born of the Cold War interest in and fascination with the USSR was bound to make ripples on the Australian intellectual and literary scene. Grishin’s lectures and networking gave impetus to the interest in Dostoevsky in Australia and focused a potentially existing interest in Dostoevsky’s works among the Australian post-war intelligentsia. These included prominent Australian poet, A.D. Hope (Alec D. Hope); Alexander Boyce Gibson, the legendary professor of philosophy and chair of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Melbourne from 1935 to 1966; English major student, David Hanan and future film critic, who became a world expert on Indonesia cinema; the future Australian writer, Robert Dessaix (studying Russian and writing originally under the name of Robert Jones) and many others, including Australian historian Manning Clark and his daughter Katerina Clark, subsequently a prominent professor of Slavic Studies in the USA. People in Australia began to talk about and to publish on Dostoevsky. Boyce Gibson, who did not read Russian, cited Grishin’s works in translation. In tandem with the publication of Grishin’s books – Dostoevsky: Man, Writer and Myths (1971), Molodoi Dostoevsky (Young Dostoevsky – published posthumously in 1977), there appeared a series of reports, books [2], translations [3] and articles [4] belonging to these Pleiades of Australian scholars. The main outlet for these publications was the journal established by Nina Christesen under the name of Melbourne Slavonic Studies (1965-1985), subsequently renamed Australian Slavonic and East European Studies (ASEES), to reflect the diversification of Russian into different Slavic languages and disciplines. The journal is still published today [5]. In 1980, the author of the present article had the honour of being asked to guest edit a commemorative issue on Dostoevsky, on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the writer’s death in 1881.[6]

Dostoevsky in Australia and the International Dostoevsky Society

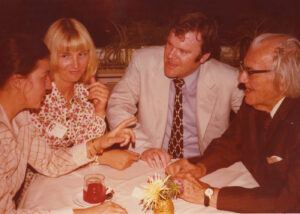

Australian Dostoevsky studies acquired an international profile with the formation of the International Society for the Study of the Life and Work of Dostoevsky or International Dostoevsky Society (IDS) for short. Until today, the IDS remains the leading Western international forum and network of international scholars engaged in the study of Dostoevsky’s life and works. This forum had its genesis in Australian Dostoevsky studies. The fact is noted in the annals of the IDS that Dmitry Grishin took the initiative, as a representative of Australia at the 1968 Congress of Slavists in Prague, to start negotiations about the establishment of an international society on Dostoevsky, which would coincide with the 150th anniversary of Dostoevsky’s birth in 1971. As a result of Grishin’s efforts, as Rudolf Neuhäuser writes in the IDS Bulletin in 1974, researchers from 16 countries gathered in Bad Ems in September 1971, where the IDS was formed. Grishin was elected first Vice President. He managed to take part in only one more IDS symposium, in St. Wolfgang, in 1974. He had a heart condition and passed away on September 19, 1975 from a heart attack.

Structuralism in Australian Dostoevsky Studies

Even before the death of D.V. Grishin in 1975, the critical approaches of Structuralism and Hermeneutics emerged on the world stage of Dostoevsky studies, advanced mainly by German, Australian and American Slavists, who embraced the legacy of Mikhail M. Bakhtin, after the publication in 1963, in Moscow, of the second edition of his book, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. In 1965, Horst-Jürgen Gerick (Heidelberg U) published a seminal monograph on Dostoevsky’s Adolescent (Raw Youth) [7], and in 1973, Wolf Schmid (Hamburg U) published his PhD on the structure of narrative in Dostoevsky’s short fictions [8]. Gerigk investigated the problem of a hermeneutic reading of this least studied of Dostoevsky’s major novels while Schmid provided a model of the narrative text derived from Prague Structuralism and Bakhtin’s theory of discourse and the polyphonic word in the novel.

Schmid’s (Bakhtinian) model of the narrative text provided an impetus for the evolution of an Australian Structuralist direction in Dostoevsky studies. In 1979, the author of the present survey (Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover), who completed her graduate studies at the University of Melbourne shortly after the death of D. V. Grishin, published her doctoral dissertation on the narrative structure of Dostoevsky’s Demons [9], in which she discussed the narrator’s techniques and information apparatus and how these devices were not ends in themselves but were used in the interest of a meta-theme, which is present in all of Dostoevsky’s major novels: the theme of the structure of meaning and phenomenology of perception[10]. This theme was treated separately in her early study entitled “Dostoevsky’s Major Novels as Models of Meaning” [11]. Another innovative direction in Dostoevsky research in Australia, which can be considered an extension of Structuralism, is the interest that emerged in Dostoevsky and psychoanalysis. In 1978, the book by Masha Kravchenko [12] appeared, in which psychoanalysis is presented as a historical context for the study of Dostoevsky’s works. In 1989, Vladiv-Glover published a paper on “Dostoevsky’s Positively Beautiful Man and the Existentialist Authentic Self: A Comparison” [13], using Abraham Maslow and Freud as theoretical contexts for Dostoevsky’s anthropology.

In 1993, Vladiv-Glover embarked on a deconstructive analysis of The Brothers Karamazov, using psychoanalysis to illuminate the metaphysics of subjectivity and representation. Vladiv-Glover published her analysis of Sigmund Freud’s article on Dostoevsky and Parricide (1928) [14], in which she critiques Freud’s essay as flawed because it is based on the distorted testimony of Dostoevsky’s early biographers (Strakhov and Miller) while also relying on the fictional motivation in Dostoevsky’s novel as biographical “factual” material on which Freud undertakes to analyse Dostoevsky’s own psychology. While Freud had sufficient insight into Dostoevsky’s fictional work, he did not choose to engage in literary criticism, but instead pursued his interest in the Oedipus complex, which he identified correctly as the backbone of the plot of the novel. However, he took this plot out of the fictional context of the novel in order to illustrate the presumed structure of Dostoevsky’s personality. This methodology of reading life through fiction or vice versa goes against the grain of the Formalist and Structuralist tenets about the autonomy of a work of fiction (expounded in the narratological model of the literary work). Despite this methodological flaw in Freud’s analysis – putting Dostoevsky’s novel “on the couch” instead of Dostoevsky himself – Freud’s article contains a valuable psychoanalytic lead into the structure of Dostoevsky’s novel. When Freud discloses that the murder of the father is not the murder of an actual father but of a virtual, imagined/imaginary one, he is positing the unconscious as a locus of action of the novel which has far reaching implications for Dostoevsky’s poetics. The paper also claims that Freud’s model of the Oedipus complex leads to the insight that the four Karamazov brothers are one subject, one personality, whose rite of passage through different phases of the Oedipus complex on its way to maturity as a fully-fledged subject of the unconscious, is witnessed by the reader.

Australian Dostoevsky Studies, Poststructuralism and Comparative Literature

Vladiv-Glover widens the scope of her psychoanalytic critical approach to Dostoevsky’s fiction by venturing into poststructuralist theory of desire and the gaze. This is explored in her monograph, published in Serbian as Romani Dostojevskog kao diskurs transgresije i požude (Belgrade: Prosveta, 2001) [Dostoevsky’s novels as discourse of desire and transgression][15]. Both concepts – desire and the gaze – are part of the phenomenology of the subject (consciousness) which goes back to Hegel’s dialectic of desire and language. This new theoretical framework is used by Vladiv-Glover in many of her published papers, but synthesised in her monograph – Dostoevsky and the Realists: Dickens, Flaubert, Tolstoy. (New York: Lang, 2019), into a representation of subjectivity as content of Russian and European Realism, forming part of a universal cultural paradigm in the 19th century [16]. From this study also emerges Dostoevsky’s new radical poetics of Realism, grounded in the representation of the world as an aesthetic (sensuous) picture or vision, constructed by the psychic mechanism of “the gaze” and driven by desire in the unconscious – in short, a poetics of the unconscious.

Post-structuralist trends in Australian Dostoevsky scholarship are taken up by postgraduate students at Monash University who have taken Dostoyevsky courses at undergraduate level in Slavic Studies and in the Centre for Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies in the 1990s, in which Vladiv-Glover introduced courses on Dostoevsky as part of the European canon. The theoretical context of Comparative Literature and Continental Philosophy have tended to provide the framework for Dostoevsky studies by Australian graduates. Australia’s geographic position outside the European region, and as a country in which European civilization is only 200 years old, has inspired a special approach in its engagement with the literary matrix of the European canons. Australian Dostoevsky studies have adapted to the condition of comparative isolation from Europe and the Slavic world and have opted for an interdisciplinary approach. The interdisciplinary approach to literary studies, which was championed by the Russian Formalist in 1914-1916, dictates that the writer’s work should be studied as a total structure and a total unified aesthetic message, which is independent of extra-literary biographical and socio-historical material on first principle. The context for such an approach is aesthetics – intertextuality and the study of form as content – rather than sociology, anthropology and socio-historical analysis relying on extra-literary material as ‘proof’. It means looking at the Russian writer in the context not only of Russian literature but of other literary canons with which the writer had contact or which are contiguous to his aesthetics. Consequently, Dostoevsky’s “Russian man” is interpreted not in the literal sense, but as a metaphor meaning a universal “personality” or “subjectivity” with an individual self-awareness or self-consciousness grounded in the unconscious. Because according to Freud the unconscious is historical, the formation of self-awareness or self-consciousness takes place through language and writing, which are, by definition, ‘national’ – ‘ours’, ‘native’, like the native language and native culture. The self is therefore a discourse grounded in other discourses of its time. This is how Dostoevsky’s “pochva” concept is interpreted in Vladiv’Glover’s writings. Instead of pointing to a “nationalist ideology”, the “Russian man” in Dostoevsky’s literary works – whose truth value is incontestable as it is a matter of hermeneutic procedure – is the bearer of European cultural values, which he draws from the cultural “archive” or “library” of European discourses of the Enlightenment and modernity, grounded in the concepts of Reason and personal freedom. Ultimately, Dostoevsky’s much mentioned “Russian man” is a metaphor for a “universal man” or “Hegelian man” in the sense of a modern subject of language – a Hegelian subject, grounded in unconscious drives – the death drive and the sex drive, in whose domain the concept (Begriff) or meaning is born. This “universal man” brings Russia into the “world-historical process” (to speak with Hegel), at least for the brief “moment” between Peter the Great’s Reforms and the 19th century.

Post-structuralist interpretations of Dostoevsky’s works amongst Australian graduates are deconstructive[17], which does not mean ‘destructive’ (as is thought in the popular use of the concept of “deconstruction”), but constitute re-readings or reinterpretations through new models of thinking, which appear in the theory of Michel Foucault or Jacques Derrida on sexuality, the authority of text, or through the rethinking of the European phenomenological canon in Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis or Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language.

This interdisciplinary study of Dostoevsky’s work has proven to be influential and productive among young Australian researchers, enrolled not only in Russian and Slavic courses but in English and Philosophy Departments.

Australian Dostoevsky Studies and The Dostoevsky Journal

In 2000, The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review came to Australia, with Vladiv-Glover becoming chief editor. The journal was published as a new series by the Slavic publisher, Charles Schlacks Jr in California.

A major attraction for Dostoevsky students in Australia and in the international Dostoevsky research forum has been the existence and continuity of The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. The inaugural issue of 2000 was supported by Monash and Melbourne postgraduates. In sympathy with the direction of Dostoyevsky studies in Australia, the journal “is devoted to the study of Dostoevsky’s work within the framework of postmodernism, post-structuralism and phenomenology, with the aim of expanding the boundaries of Dostoevsky’s poetics” as well as re-evaluating the historical (aesthetic) context of his work. In the 23 issues of the journal (2000-2022), many international scholars have been attracted to this editorial platform and have published articles based on new theoretical directions in Dostoevsky research.

The philosophical aspect of Dostoevsky’s creative work was studied within the framework of a symposium organized in St. Petersburg on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the New School of Religion and Philosophy. A special issue of The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, whose guest editor was Natalia Pecherskaya [18], was dedicated to this symposium. Israeli researcher, Roman Katsman, published his deconstructive analysis of the novel The Adolescent, in which he refers to the works of Rene Girard, A. Lingis, E. Levinas, but also A. Losev, who provide him with a model of being, based on the concepts of presence/absence which ground the idea of writing in the structure of the hero figure [19]. The analysis of the speech of the “other” in Bobok is the topic of the article by the German researcher, Dorothee Gelhard. The Australian Continental Philosophy scholars, Peter Mathews and Bryan Cooke, offer critical interpretations of Dostoevsky’s poetics, from Freud and Bakhtin to Julia Kristeva, deconstructing Malcolm Jones’ study of theoretical trends in Dostoevsky research after Bakhtin [20].

In 2002-2003, The Dostoevsky Journal published two papers which tackle the theme of sexuality and homo-eroticism in Dostoevsky’s creative writing. Susanne Fusso interprets the intrigue of the novel The Humiliated and the Injured as part of Dostoevsky’s convoluted efforts to introduce the theme of sexuality into his poetics [21]. Irene Zohrab sheds light on the sexuality of Stavrogin and a number of other characters in The Possessed, and also on Trishatov in The Adolescent, predicating her findings on historical intertextual documentation. She argues that Dostoevsky, while living abroad became aware of the writings of the jurist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, and his campaign for law reform in defence of ‘Urnings’, including the notorious trial of von Zastrow [22]. Zohrab had already tackled the theme in earlier publications which renders her a pioneer in the mapping of (homo)sexuality as part of Dostoevsky’s artistic legacy [23].

The Dostoevsky Journal has been one of the first Western academic platforms to include postmodern theory as a frame for Dostoevsky’s ethics. The late Andrew Padgett (16 August 1978 – 4 January 2015), whose premature death impoverished the field of Comparative Literature in Australia, interpreted the personality of the underground paradoxalist as a feature of the realm of nothingness or “infinite potential”, connecting these concepts with the theory of the post-structuralist moralist Giorgio Agamben [24].

Australian Dostoevsky studies also attracted scholars from English departments. Thus Nicholas Terrell, a scholar at Sydney University, poses the question of secular idealism in Notes from the Underground, in which Terrell sees a kind of disease disguised by the underground paradoxalist through rhetoric [25]. Jonas Cope, also an ‘Anglist’, produced a comparative analysis of Notes from the Underground and a 1952 novel by African-American writer Ralph Ellison [26]. Cope concludes that the saving repentance of the paradoxalist leads the reader of Dostoevsky to a positive assessment of art as a social act, while the ending of Ellison’s novel is not convincing. Thus, for Cope, we infer, Dostoevsky’s aesthetics represents a benchmark for aesthetic evaluation of future art.

In recent times, in keeping with emerging trends in literary research, The Dostoevsky Journal also published analyses on sociological topics adopting the theoretical frame of feminist criticism. Andrea Zink, a scholar at the University of Basel (Switzerland), interrogated the role of prostitution in Russian literature, expressed through the images of fallen women in the works of Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky [27]. Zink comes to the conclusion that despite all attempts to create an image of a nationally united and socially harmonious Russia, Dostoevsky (like Tolstoy, but unlike the programmatically ideological Chernyshevsky) cannot renounce his class (bourgeois) point of view, according to which the fallen woman attains neither social redemption, nor unity with the Russian intelligentsia, whom she is charged with saving.

In 2014, The Dostoevsky Journal: A Comparative Literature Review passed to Brill. In 2020, the journal was listed in Scopus. Since then, there has been interest by more young scholars from Europe, Russia and the USA who are responding to the scope of the journal to situate Dostoevsky in the context of postmodernism, post-structuralism and phenomenology and to demonstrate how much Dostoevsky is still our contemporary.

Since it has always had a policy of publishing in Russian as well as English, the journal has received strong academic support from Russian scholars in Russia, where translation is not an easy option. The late Natalia Zhivolupova (16.8.1949 Vladimir – 28.4.2012 Nizhny Novgorod), who, in sympathy with Bakhtin’s ethics, was one of the first among Russian scholars to treat the theme of “the other” in Dostoevsky’s fiction. She also pioneered research into a genre she called the “confession of the anti-hero” [28]. Her research legacy is carefully nurtured by her husband, Alexander Kochetkov, which continues to feature in current Dostoevsky research. Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Literature Institute “Pushkinskii dom” and their graduates have brought their valuable archival research to The Dostoevsky Journal. Konstantin Barsht has published on “The Symbolism of Oak Leaves in Dostoevsky’s Notebooks (Drafts) to Crime and Punishment” [29], using illustrations in colour. Barsht’s graduate student, Igor Kravchuk, has published on “The Ghost of the Nephew: Napoleon III in Demons” [30], decoding an important literary-historical allusion in Dostoevsky’s novel. Olga Shalygina (A. M. Gorky Institute of World Literature RAN) has published her research on Dostoevsky and Andrei Bely in the context of the fin-de-siècle Russian philosophy of V. V. Rozanov on «сейчас бытие» [“presentness being”].

The platform of the journal has allowed Dostoevsky studies in Australia to be enriched by an ongoing dialogue with scholars around the world, East and West, which has greatly contributed to Australian academia serving a multicultural Australian civil society.

Contributions of Dr Irene Zohrab, New Zealand Representative of IDS and Affiliate of ADS, Victoria University of Wellington – Te Herenga Waka, New Zealand.

In addition to the critical approaches enumerated above, Australian Dostoevsky Studies, through the medium of The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, profited enormously from the research of Dr Irene Zohrab, formerly Associate Professor at Victoria University of Wellington – Te Herenga Waka and editor of the New Zealand Slavonic Journal, as well as an early Associate Editor and now Co-Editor of The Dostoevsky Journal.

The wide-ranging subject matter of Zohrab’s research is a reflection of the wide-ranging courses that Slavists in Australasian universities were expected to cover.

Some of the “firsts” in research topics and archival research contributed by Irene Zohrab include work on the journal The Citizen as edited by Dostoevsky [31]; on the impact on Dostoevsky of the British social philosophers, including Buckle, Mill, Spencer and Darwin [32]; and on the correlation between the cultural and philosophical foundations formative to the writings of Dostoevsky and Kierkegaard, viewed as precursors of existentialism, with special attention to the problem of censorship both writers faced in their respective countries [33].

Supporting Vladiv-Glover’s re-evaluation of Dostoevsky’s conception of “pochva” [34], Zohrab delved into the antecedents of Dostoevsky’s pochvennichestvo [“soil” taken as an ideology] in A. A. Grigor’ev organicist aesthetics and in A.N. Ostrovsky, the ‘young editors’ of M. Pogodin’s Moskvitianin, who were allies of the Slavophiles, and indebted to German philosophy. [35] In addition, Zohrab illuminated Dostoevsky’s interest in the dramatic genre and its relationship to narrative, and these genres’ respective means of encompassing debate, analysis and the expression of authorial voice. Dostoevsky’s choice of the polyphonic method in narrative had the advantage of protecting him from censors issuing an empirical judgement on the author’s position.

Her investigation of Dostoevsky’s ambivalent attitude to Turgenev directed attention to the evolution of the portrait of Karmazinov in Demons [Besy] and some previously unknown evaluations by Dostoevsky of Turgenev. The rhetoric of Dostoevsky’s Pushkin Speech (1880), regarded as his ‘legacy to the Russian people’, was tracked by Zohrab to Dostoevsky’s response to material on Pushkin published in 1872-1874 and the celebration of the unveiling of a monument to the poet. [36]

At the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of teaching Russian language and literature in Australia at the University of Melbourne in 1996, the topic of Zohrab’s report on Dostoevsky’s acquaintance with Protestantism was based on evidence found in The Citizen. Her discovery of Dostoevsky’s input into the editing of the sermons and the book on the Eastern Church by Arthur P. Stanley, the Dean of Westminster, led Zohrab to demonstrate the possible influence of these discourses on the Brothers Karamazov [37].

Zohrab has published widely on Dostoevsky and Britain, including on the discord regarding the campaign and conquest of Khiva [38]. More recently in The Dostoevsky Journal, vol. 19, 2018 she wrote on “Tom Brown’s Schooldays as a Supplement to The Citizen (Grazhdanin) and Dostoevsky’s Later Works of the 1870s”, basing her insights on the first translation of the Victorian novel into Russian, published by The Citizen as a Supplement.

In The Dostoevsky Journal, vol. 20, 2019 she analysed Dostoevsky’s evolving attitude to humanism. Her forensic analysis, based on new material, of Dostoevsky’s first London visit, brought new insights into Dostoevsky’s Winter Notes of Summer Impressions: these results were published in the 2021 issue of Dostoevskii. Materialy i issledovaniia [39]. Some of her attributions ascribing partial authorship to Dostoevsky have been included in the more recent Works of Dostoevsky in 18 volumes, in the section on Joint Authorship (Kollektivnoe) [40].

Zohrab has introduced English-speaking readers of Dostoevsky to numerous of his shorter works and journalism in English translation, working in collaboration with the New Zealand translator David Foreman. As an early member of the International Dostoevsky Society and its New Zealand representative, Irene Zohrab has contributed to the recording of the history of the IDS based on her own recollections [40]; as an Affiliate of the Australian Dostoevsky Society, she is also part of the history of the ADS as an Australasian institution.

Summary

Mediated by the small collective of the Australian Dostoevsky Society, now augmented by the New Zealand affiliate, Dostoevsky research continues to exist despite little institutional support: only five universities in Australia and one in New Zealand offer Russian courses in full or reduced format, compared to upwards of six universities in each of these two countries in the 1950’s-1990s. Bookshops in Australia still stock freshly printed new and old editions of Dostoevsky’s novels in English translation. Although Dostoevsky is no longer taught in high schools (along with other writers of the ‘classical’ European canons), there is evidence of a wide interest of the reading public in his works.

The research into Dostoevsky has always been difficult in Australia and New Zealand not because of the lack of material infrastructure – our libraries are excellent and acquire material around the globe – but because of the distance to conferences and to a live exchange with a wider community of scholars. This absence of a critical mass of people in the Southern hemisphere has meant that the researchers did not walk into a country where Slavic and Russian were already established. When they started their careers in Russian and Dostoevsky studies, they also had to be the makers of a new literary and critical tradition and the institutions which had to support these.

Of course, this had consequences for the output which is not as extensive as say, that of researchers at RAN or at the universities in the USA; but that does not diminish the pioneering effort of those who were on the ground nor the input they have had theoretically and in research scope to the world of Dostoevsky studies.

For being on the margins may have some advantages. While following the debates in ‘mainstream Dostoevsky countries’, researchers in Australia and New Zealand have pursued their own directions in the application of new theoretical models – structuralism, psychoanalysis, phenomenology – to the study of Dostoevsky’s creative output and have been the first to challenge some of the received myths about Dostoevsky’s journalistic output.

In the world of today it is more important than ever to be careful readers of any texts but in particular of Dostoevsky’s fictional and creative texts which have been appropriated over the years for many causes and purposes outside the sphere of aesthetics in which they were generated. It is equally important to acknowledge the official context and to assess the truth value of Dostoevsky’s journalism. For too long, Dostoevsky scholarship – despite impulses especially form New Zealand – has ignored the conditions of the harsh Tsarist censorship which obtained throughout Dostoevsky’s career as a journalist. It is as a result of the catastrophic experience of a commuted death sentence and ten years of Siberian exile that Dostoevsky found it necessary or expedient to adopt a public persona which at face value appeared to be sympathetic to Tsarist government policy, and in agreement with the ideology of “самодержавие, церковь, семья» [“autocracy, church, family”]. This was elevated by generations of critics into Dostoevsky’s alleged «почва» [“soil]” doctrine, by uncritical readings of many of his journal articles but above all by connecting, out of contexts, segments of texts from different registers – the factual and the fictional, creating a “factional” amalgam. What is systematically ignored is that what Dostoevsky wrote in his Diary of a Writer, his journals and his letters was for public consumption. It was stylized and directed to a Russian quasi-conservative Reader who was also partly progressive without being revolutionary or subversive. This is the Reader Dostoevsky constructed in his journalism – a reader of “his time”, not a 20th century or 21st century anti-Neoliberal with a high bar on Human Rights. Dostoevsky did not care about this reader of posterity – he was more concerned about shielding his revolutionary novels from the 19th century Russian censor so that these novels could reach posterity. Dostoevsky was a master stylist, who could adopt many voices and simulate many discourses. While it is an undisputed fact that he followed Russian social and political life with passion, it is doubtful that he used it as a political scientist, a sociologist or an ideologue. His publicist work is not particularly analytical nor is it, for the most part, well written and organised. It is haphazard, like a writer’s laboratory. All the “facts” of Russian social life were material for his novels – they were the bricks and mortar – the fabric of his new prose which portrayed Russian history as genealogy in Hegel’s sense of the term and not as archeology. The messages of his novels are complex aesthetic messages, directed at a new as yet perhaps unformed Russian reader – not the same one as the ideologically limited reader of his publicist works. Many of his contemporaries anticipated this “New Reader”, they “read” the aesthetic messages of his novels or were able to intuit their newness and importance; but on the whole Dostoevsky’s fiction overshot the horizon of expectation of the public of his day. Today is another day, and the time has arrived for another Reader, the Reader actually constructed by Dostoevsky’s artistic texts. These texts are radically innovative, whose poetics anticipates the poetics of European and Russian Modernism – the entire artistic production of the 20th century. Dostoevsky did not need his journalism and his Diary of a Writer in order to “make his aesthetic messages clearer” – and neither do we. If Dostoevsky’s novels were to be just fictionalized expressions of what he wrote in Diary of a Writer, his journals and his letters, we would have ended up with a dostoevskian socialist realist monologic novel, not a polyphonic novel. It is particularly absurd when commentators in East and West try to squeeze Dostoevsky’s so-called “world view” into a schema, constructed out of random quotations plucked out of his publicist writings and cobbled together, out of context, into a pretend-model of analysis. It is the same as trying to fit the man to a coat made by the artless tailor in the folktale. It is precisely the lack of hermeneutic analysis – or close reading of texts – which leads to the ideological excesses in the Dostoevsky exegetical industry. It takes the line of least resistance in using the recipe: take the fictional plots and the dialogues and build an edifice on the correspondences between the pronouncements of fictional characters and the utterances in Diary of a Writer – and you know immediately, without doubt, what Dostoevsky thought. It is like the evangelical preachers on late-night TV who claim to have a direct telephone line to God. Precisely because Dostoevsky is such a significant writer who belongs not only to Russia and the Russian literary tradition but to the European literary culture and world literature, that it is crucial to “save” him from ideological (mis)appropriations of all kinds which happen through bad (mis)interpretation of his fiction. The reductionism of Dostoevsky’s creative opus to ideology by those who, by education and training, should possess the means to delve into his literary works in truthful manner, spreads more harm than one can easily quantify. Because myths spread even faster than truth – as Dostoevsky showed so aptly in Demons [Бесы].

The view of Russian history which Dostoevsky proffers in his novels is so radical and so subversive, that had he tried to couch this in a direct confession de fois, he would have got another ten years of exile from his second Tsar. It is a good thing that the Russian censor did not read Hegel and so could not hear echoes of the German philosopher in Dostoevsky’s prose. The task of hearing these echoes – a daunting task in view of the complexity of Dostoevsky’s and Hegel’s writings as opposed to subsequent simplifications of their dialectic by what Nietzsche has called the “marketplace” – remains the most pressing task for Dostoevsky scholarship.

NOTES

[1] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover taught in the Centre for Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies and was Acting Head and Head of Slavic Studies at Monash University at various times until 2013. She is editor-in-chief of The Dostoevsky Journal: A Comparative Literature Review (Brill). An earlier Russian version of this paper was published as Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, “Dostoevsky Studies in Australia 1956 – 2012” in: Sobranie sochinenii i pisem F. M. Dostoevskogo, 2-e, ispravlennoe i dopolnennoe izdanie. Sbornik, posviashchennyi teme “Vospriatie i izuchenie tvorchestva F. M. Dostoevskogo v mire”. Glavnyi redaktor Nina Fedotovna Budanova, (StPeterburg: “Nauka”, 2013).

[2] Alexander Boyce Gibson, The Religion of Dostoevski, (SCM Press Ltd.:London, 1973); Alexander Boyce Gibson, “The Riddle of the Grand Inquisitor,” Melbourne Slavonic Studies, No. 4 (1970):46-56.

[3] F M Dostoevsky, Poor Folk. Translated and with an Introduction by Robert Dessaix. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Ardis, 1982).

[4] David Hanan, “Crime and Punishment: The Idea of the Crime,” The Melbourne Critical Review, No. 12 (1969): 15-28.

[5] In 2012, the editorial staff moved from the University of Queensland, where it was headed by John McNair, to the University of Melbourne, where Robert Lageberg, head of the Russian Language Department, became the editor-in-chief.

[6] Slobodanka Vladiv, Dostoevsky Commemorative Issue. Melbourne Slavonic Studies, Vol 14 (1980). Guest Editor, 100 pp.

[7] Horst-Jürgen Gerigk, Versuch über Dostoevskijs ‘Jüngling’: Ein Beitrag zur Theorie des Romans, Forum Slavicum, ed. Dmitrij Tschižewskij, Band 4 (München: Wilhelm Fink, 1965).

[8] Wolf Schmid, Der Textaufbau in den Erzählungen Dostoevskijs, Beiheft zu Poetica, ed. Karl Maurer, Heft 10 (München: Wilhelm Fink, 1973).

[9] Slobodanka B. Vladiv, Narrative Principles in Dostoevsky’s Besy: A Structural Analysis, (Berne: Peter Lang, 1979).

[10] The theme of the construction of meaning is treated in a paper which examines the function of associative links and writing (as inscription) in Porfiry Petrovich’s hypothesis building in Slobodanka Vladiv, “The Use of Circumstantial Evidence in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment”, Candian-American Slavic Studies, Vol 12, Issue 3 (1978), pp. 353-370.

[11] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, “Dostoevsky’s Major Novels as Models of Meaning,” Dostoevsky Studies (Journal of the International Dostoevsky Society), Vol 9, No.1 (1989): 157-162.

[12] Maria Kravchenko, Dostoevsky and the Psychologists. (Amsterdam: Verlag Adolf M. Hakkert, 1978). This direction has its continuation in the later studies of the American scholar, James Rice (who passed away in 2011).

[13] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glove, “Dostoevsky’s Positively Beautiful Man and the Existentialist Authentic Self: A Comparison,” Canadian American Slavic Studies, Vol 23, No. 3 (Fall 1989): 313-329.

[14] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, “Dostoevsky, Freud and Parricide: Deconstructive Notes on Тhe Brothers Karamazov,” New Zealand Slavonic Journal (1993): 7-34. (Invited paper to open new series of journal.)

[15] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, Romani Dostojesvkog kao diskurs transgresije i požude. (Beograd: «Prosveta”, 2001), 213 pp.

[16] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, Dostoevsky and the Realists: Dickens, Flaubert, Tolstoy. (New York: Lang, 2019); see also an earlier version in Serbian Poetika realizma: Dostoejevski, Flober, Tolstoj. (Beograd: Ariadna, 2010).

[17] Vladiv-Glover, “The Accidental Family in The Adolescent and Wittgenstein’s Family Relations: The Novel as Model of Meaning,” in: Aspects of Dostoevsky’s Poetics in the Context of Literary-Cultural Dialogues. Editors: Katalin Kroó, Géza S. Horváth, Tünde Szabó. Volumne 3 Dostoevsky Monographs Series. (Sankt-Peterburg:” Dmitrii Bulanin,” 2011), pp. 59-74.

[18] Compare The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 2 (2001): 1-152.

[19] Roman Katsman, «Dostoevsky’s A Raw Youth: Mythopoesis as the Dialectics of Absence and Presence (From Capital to Writing),” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 1 (2000):85-95.

[20] Malcolm Jones, Dostoevsky after Bakhtin: Readings in Dostoevsky’s fantastic realism. (Cambridge UP, 1990), see the critique of this publication in Peter Mathews and Bryan Cooke, “Dostoevsky: Expression in Silence”, The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, Vol.1 (2000): 1-9.

[21] Susannne Fusso, “Secrets of Art” and “Secretes of Kissing”: Towards a Poetics of Sexuality in Dostoevsky,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 3-4, 2002-2003: 47-58.

[22] Irene Zohrab, “‘Mann-männliche’ Love in Dostoevsky’s Fiction (An Approach to The Possessed): With some Attributions of Editorial Notes in The Citizen. First Instalment”, The Dostoevsky Journal, 3-4 (2002-2003): 113-226;

[23] Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevsky and Meshchersky”, Australian Slavonic and East European Studies, 12 (1), (1998): 115-134; Irene Zohrab, “‘The Last Little Page’: Humour in The Citizen during F.M. Dostoevskii’s editorship (with some attribution)”, New Zealand Slavonic Journal, (1997): 297-328; Irene Zohrab, “Refashioning masculine gender norms on the pages of The Citizen during Dostoevsky’s editorship”, in Slobodanka M. Vladiv-Glover (Guest Editor), Modernism and Postmodernism. Soviet and Post-Soviet Review, (2001 [2002]): 333-362; Irene Zohrab, “The Correspondence between Prince V.P. Meshchersky and Grand Duke Nikolai Alexandrovich. A Friendship, its Aftermath and the Creation of Scandals”, in Irene Zohrab (ed), Slavonic Journeys across Two Hemispheres, (Wellington: Victoria University, 2003): 237-280.

[24] Andrew Padgett, “Beyond Dostoevsky: The Discourse of Non-Existence”, The Dostoevsky Journal, vols. 3-4 (2002-2003): 79-92.

[25] Nicholas Terrell, “Soap Bubbles and Inertia: The Underground Man’s Dependence on Rhetoric, Narrative Frameworks and Scepticism as a Syndrome of Secular Idealism,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, Vol. 7 (2006):1-29.

[26] Jonas Cope, “Shaking off the Old Skin: The Redemptive Motif in Ellison’s Invisible Man and Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, Vol. 7 (2006):75-91.

[27] Andrea Zink, “What is Prostitution Good For: Dostoevsky, Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy and the ‘Woman Question’ in Russian Literature,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, Vol. 7 (2006):93-106.

[28] Natalia Zhivolupova, «Другой в художественном сознании Достоевского и проблема эволюции исповеди антигероя», The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, Vol. 2 (2001):37-54.

[29] Konstantin Barsht, “The Symbolism of Oak Leaves in Dostoevsky’s Notebooks (Drafts) to Crime and Punishment”, The Dostoevsky Journal: A Comparative Literature Review, vol 22 (2021):5-44.

[30] Igor Kravchuk, “The Ghost of the Nephew: Napoleon III in Demons”, The Dostoevsky Journal: A Comparative Literature Review, vol 22 (2021):150-184.

[31] Irene Zohrab, “The contents of ‘The Citizen’ during F.M.Dostoevsky’s editorship: Uncovering the authorship of unsigned contributions. Dostoevsky’s quest to reconcile the ‘flux of life’ with a self-fashioned Utopia”, The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 5, (2004): 47-216; Irene Zohrab, “Documents, New Material and Translations. Dostoevsky’s Editorship of Meshchersky’s The Citizen (Grazhdanin): Issues Nos 31 to 52, 1873. Uncovering the Authorship of Unsigned Contributions (with Emphasis on Material Relating to Religion and the Church).” Part 2, New Zealand Slavonic Journal, 39, (2005): 216- 260. See also NZSJ (2004) and (2006).

[32] Irene Zohrab, “Darwin in the pages of The Citizen during Dostoevsky’s editorship and echoes of Darwinian fortuitousness in The Brothers Karamazov”, The Dostoevsky Journal. A Comparative Literature Review, vols.10-11, (2009-2010): 79-96; Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevskii and British Social Philosophers”, in W.J. Leatherbarrow (ed), Dostoevskii and Britain. (Oxford/Providence, USA: Berg Publishers, 1995): 177-206; Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevsky and Herbert Spencer”, Dostoevsky Studies, 7, (1986): 45-72; Irene Zokhrab, “Dostoevskii i Darvin”, in Dostoevskii i mirovaia kul’tura, Almanakh №28, edited by K.A. Stepanian (Moscow: 2012): 30-65; I. Zokhrab, “‘Evropeiskie gipotezy’ i ‘russkie aksiomy’”. Utilitarism v Rossii (F.M.Dostoevskii i Dzh.S. Mil’)” [‘“European Hypotheses” and “Russian Axioms”. Utilitarianism in Russia (F.M. Dostoevsky and J.S. Mill)”], Russkaia Literatura, (Sankt-Petersburg: 4, 2000): 37-52; I. Zokhrab, “Otnoshenie Dostoevskogo k britanskim ‘predvoditeliam evropeiskoi mysli’ (Statia vtoraia ‘Dostoevskii i Gerbert Spenser’)”, in Boris Tikhomirov (ed), Dostoevskii i mirovaia kul’tura, (Sankt Peterburg: 2003). Issue19: 105-131.

[33] Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevsky and Kierkegaard in the Context of State Censorship. Problem Statement (With a Postscript on the ‘Hostage Syndrome’)”, Dostoevsky Journal, vols. 14-15 (2013-2014): 65-109; I. Zohrab, “Popytka ustanovleniia vklada F. M. Dostoevskogo v redaktirovania statei sotrudnikov gazety-zhurnala Grazhdanin v ramkakh tsenzury togo vremeni. Postanovka problem” in Dostoevskii i zhurnalism, edited by Vladimir Zakharov, Karen Stepanian, Boris Tikhomirov (St. Petersburg: Dmitry Bulanin, 2013): 143-69; Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevsky and Censorship” in Dostoevsky in Context, edited by Deborah Martinsen and Olga Maiorova (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015):293-302; Irene Zohrab, “From Zimnie zametki o letnikh vpechatleniiakh to Prestuplenie i nakazanie: decoding Dostoevsky’s narrative strategies to write in a way “passable by censorship” (tsenzurnee)”, XVI Symposium of the IDS. “Crime and Punishment” 150 years since its publication. Abstracts (Granada, 2016): 25-26 (Forthcoming 2022).

[34] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, “Dostoevsky’s “Pochva” [“Soil”] and “Russian Identity” in Phenomenological Perspective: A Reading of the 1860 “Notice” to Vremia, The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, Vol. 14-15 (2013-2014): 52-64.

[35] Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevskij through the prism of his reception of Ostrovsky’s works” in Actualité de Dostoevskij, (Genova, La Querzia Edizoni, 1982): 119-44; Irene Zohrab, “ ‘The Slavophiles’ by M.P. Pogodin. An introduction and translation”, New Zealand Slavonic Journal, (1982): 29-87.

[36] I. Zokhrab, “F.M.Dostoevskii i A.N. Ostrovskii v svete redaktorskoi deiatel’nosti Dostoevskogo v ‘Grazhdanine’”, in Fridlender G. (ed), Dostoevskii. Materialy issledovaniia, 8, (Leningrad: Akademiia Nauk SSSR, 1988): 107-25; I. Irene Zohrab, “Turgenev and Dostoyevsky: a reconsideration and suggested attribution”, New Zealand Slavonic Journal, (1983): 123-42; Irene Zohrab, “Books reviewed in Grazhdanin (The Citizen) during F.M. Dostoevsky’s editorship”, Dostoevsky Studies, 4, (1983): 125-38; Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevskii as editor of ‘The Citizen’: New Materials”, in R. Neuhäuser (ed.), Polyfunktion und Metaparodie, (Dresden: Dresden University Press, 1997): 241-270; Irene Zohrab, “ ‘A Poem in Prose’: The Sexton, a forgotten text at the centre of the Dostoevsky/Leskov literary polemic”, Australian Slavonic and East European Studies, 12 ( 2), (1998): 57-82; Irene Zohrab, “Constructs of Pushkin on the pages of The Citizen and Dostoevsky’s globalisation of the ‘People’s Poet’ in the context of Russia as Europe’s ‘Other’”, New Zealand Slavonic Journal, (1999): 119-183.

[37] Irene Zohrab, “Dostoevsky’s Encounter with Anglicanism”, Australian Slavonic and East European Studies, 10 (2), (1996): 187-208; I. Zohrab. “Redaktorskaia deiatel’nost’ F.M.Dostoevskogo v zhurnale “Grazhdanin” i religiozno-nravstvennyi kontekst “Brat’ev Karamazovykh”, Russkaia literatura. (Sankt Peterburg: 3, 1996): 55 -77; I. Zohrab, “Odin intertekst v Brat’iakh Karamazovykh F.M.Dostoevskogo”, in V.N. Zakharov (ed.), Evangel’skaia tsitata v russkoi literature XVIII- XX vekov. (Petrozavodsk: Petrozavodsk University Press, 1998): 424-441.

[38] Irene Zohrab, Dostoevsky and England (2010). Victoria University, Wellington, 2010. 300pp. Irene Zohrab, “What does Dostoevsky’s contribution to articles relating to the Russian conquest of Khiva published in The Citizen in 1873-4 reveal about the writer? (With Some Attribution.)”, in F. M. Dostoevsky in the Context of Cultural Dialogues. F. M. Dostoevskii v kontekste dialogicheskogo vzaimodeistviia kul’tur. Edited by Katalin Kroó and Tünde Szabó. (Budapest: 2009): 557-565; Irene Zohrab, “Documents, New Material and Translations. Dostoevsky’s Editorship of Meshchersky’s The Citizen (Grazhdanin): Issues Nos 1 to 16, 1874. Uncovering the authorship of unsigned contributions. (With Emphasis on Material Relating to the Russian Conquest of Khiva and Relations with England)”, New Zealand Slavonic Journal, Vol 40, (2006): 162-219; Irene Zohrab, “Public Education in England in the Pages of The Citizen (1873-1874) during Dostoevsky’s Editorship, in Lesley Milne and Sarah Young (eds), Dostoevsky On the Threshold of Other Worlds, (Derbyshire, UK: Bramcote Press, 2006): 98-109; I. Zokhrab, “Obshchestvennoe vospitanie v Anglii na stranitsakh “Grazhdanina” vo vremia redaktorstva F.M. Dostoevskogo”, in V.V. Dudkin (ed), Dostoevskii i sovremennost’, (Velikii Novgorod, 2005): 90-103.

[39] Irene Zohrab, “Tom Brown’s Schooldays as a Supplement to The Citizen (Grazhdanin) and Dostoevsky’s Later Works of the 1870s”, The Dostoevsky Journal. A Comparative Literature Review, vol. 19 (2018): 1-46; A. Zokhrab, “Roman Tomasa KH’iuza «Shkol’naia zhizn’ Toma Brauna» («Tom Brown’s Schooldays») v tvorchestve F.M. Dostoevskogo 1870-kh godov”, Dostoevskii. Materialy i issledovaniia, vol. 22 (2019): 56-87; Irene Zohrab, “‘Characterisation of Belinsky’ by M.P. Pogodin published by Dostoevsky in The Citizen in response to the first issue of Writer’s Diary. (With a Translation)”, The Dostoevsky Journal. A Comparative Literature Review, vol. 20, (2019):1-22; Appendix: Translation of “Characterisation of Belinsky (Information and illumination)” by M.P. Pogodin. (Translated by David Foreman and Irene Zohrab) The Dostoevsky Journal. A Comparative Literature Review, vol. 20, (2019): 23-31. Irene Zohrab, “Palimpsest F M Dostoevskogo: Zimnie zametki v letnikh vpechatleniiakh i londonskie vystavki 1862 g.”, Dostoevskii. Materialy i issledovaniia, vol. 23 (2021): 29-85.

[40] “Kollektivnoe” in Polnoe sobranie sochnenii F.M. Dostoevskago v18-ti tomakh, Voskresen’e [2004] 2005: 266-269; “Stat’i 1873-1878”, 207-210.

[41] Irene Zohrab, “Impressions (from a New Zealand perspective) of the history of the IDS and its Symposia», Dostoevsky Studies. The Journal of the International Dostoevsky Society. Vol. 24 (2021):149-187. Illustrations: 188-215; Irene Zohrab, “Mezhdunarodnoto obshchestvo ‘Dostoevski – istoriia i nadezhdi”’ in Dostoevski: Mys”l i obraz, Tom 1 (Sofia: Istok-Zapad, 2014): 12-20; I. Zokhrab, “Vospriiatie Dostoevskogo pisateliami i sviashchennosluzhiteliami Novoi Zelandii” in Dostoevskii. Materialy i issledovaniia, 20, (St. Petersburg: Rossiiskaia Akademiia Nauk. Institut Russkoi Literatury ‘Pushkinskii Dom’, Izd. Nestor-Istoriia, 2013): 419-437.

©Revised April 2022

[1] De Bray left Monash University to take up an appointment at the School of SEES in London but returned to a chair at the ANU which was his last professorial appointment.

Dostoevsky Studies in Australia

Selected Bibliography

Избранная Библиография

Benevich, Gr. (2001) “Mat’-Syra-Zemlia i geopolitika (sviortyvanie ploskostei Fyodora Dostoevskogo) [Mother-Earth and Geopolitics (Dostoevsky’s flattening of surfaces)],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Blumenkrants, M. (2001) “Eskhatologicheskaia problema v tvorchestve F M Dostoevskogo [The eschatological problem in the works of F M Dostoevsky],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Boyce Gibson, Alexander (1973) The Religion of Dostoevski. London: SCM Press.

Christa, Boris (2006) “Raskolnikov’s Wardrobe: Dostoevsky’s Use of Vestimentary Markers for Literary Communication in Crime and Punishment,” in Sarah Young and Lesley Milne (eds) Dostoevsky on the Threshold of Other Worlds: Essays in Honour of Malcolm V. Jones (Ilkeston, Derbyshire: Bramcote Press), pp. 14-20.

Christa, Boris (2002) “The Semiotic Depiction of Disintegration of Personality in Dostoevsky’s The Double,” in K. Stepanian (ed.) XXI vek glazami Dostoevskogo—perspektivy chelovechestva: materialy Mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii sostoiavsheisia v Universitete Tiba (Iaponiia), 22-25 avgusta 2000 goda (Moskva: Graal), pp. 221-234.

Christa, Boris (2002) “Semioticheskoe opisanie raspada lichnosti v Dvoinike Dostoevskogo,” in K. Stepanian (ed.) XXI vek glazami Dostoevskogo—perspektivy chelovechestva: materialy Mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii sostoiavsheisia v Universitete Tiba (Iaponiia), 22-25 avgusta 2000 goda (Moskva: Graal), pp. 235-250.

Christa, Boris (2002) “Dostoevskii and Money.” In W.J. Leatherbarrow (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Dostoevskii. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 93-110.

Christa, Boris (2000) “‘Money Talks’: The Semiotic Anatomy of ‘Krotkaia’,” Dostoevsky Studies n.s. 4: 143-51.

Christa, B. (1997) “Vestimentary Markers as an Element of Literary Communication in The Brothers Karamazov. In “Die Brüder Karamasow”: Dostojewskijs letzter Roman in heutiger Sicht (Dresden: Dresden University Press), pp. 89-103.

Cope, Jonas (2006) “Shaking off the Old Skin: The Redemptive Motif in Ellison’s Invisible Man and Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 7: 75-91.

Fateeva, N. A. (2001) “Deistvitel’no li Dostoevskii dialogichen? O dialogichnosti i intertekstual’nosti ‘otchaianiia’ [Is Dostoevsky truly dialogic? On the dialogicity and intertextuality of ‘despair’],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Fusso, Susanna (2002-2003) “‘Secrets of Art’ and ‘Secrets of Kissing’: Towards a Poetics of Sexuality in Dostoevskii,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Gelhard, Dorothee (2000) “Das Prinzip der Partizipation am fremden Text in Dostoevskijs Bobok,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 1: 113-122.

Gerigk, Horst-Jürgen (1965) “Versuch über Dostoevskijs ‘Jüngling’: Ein Beitrag zur Theorie des Romans, ” Forum Slavicum, Dmitrij Tschižewskij (ed.), Band 4 (München: Wilhelm Fink).

Grishin, D. (1963) “The Beliefs of Dostoevsky,” Twentieth Century, vol. 17: 255 ff.

Grishin, D. V. (1971) Dostoevskii – Chelovek, Pisatel’ i Mify (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press).

Grishin, D. V. (1966) Dnevnik pisatelia F. M. Dostoevskogo. (Mel’burn: Otdelenie russkogo iazyka i literatury Mel’burnskogo universiteta).

Grishin, D. V. (1961) Aforizmy i vyskazyvania F. M. Dostoevskogo (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press).

Кацман, Роман (2002-2003) “Между Пусьмом и Документом или Критические Заметки о Жизни Знаков в Подпостке Достоевского,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Kholodov, A. B. (2001) “Mifopoetika romanov F M Dostoevskogo: Dialog i kontekst [Mythopoetics of Dostoevsky’s novels: Dialogue and Context],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Kravchenko, Maria (1978) Dostoevsky and the Psychologists (Amsterdam: Verlag Adolf M. Hakkert).

Lane, David (2005), “A Reading of Dostoevsky’s The Double Through the Psychoanalytic Concepts of The Self and The Other,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 5.

Mathews, Peter David (2002-2003) “That Which Exceeds,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Mathews, Peter and Bryan Cooke (2000) “Dostoevsky: Expressions in Silence,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 1: 1-9.

Minney, Penelope (2001) “Dostoevsky’s Dialogic Imagination and the British School of Radical Orthodoxy,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Nogovitsin, Oleg (2001) “Zlo v khristianstve i bunt Ivana Karamazova [Evil in Christianity and Ivan Karamazov’s Rebellion],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Padgett, Andrew (2002-2003) “Beyond Dostoevsky: The Discourse of Non-Existence,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Rusniak, I. A. (2001) “Mifologicheskoe myshlenie v dialogicheskoi strukture teksta Dostoevskogo (Bratia Karamazovy)[Mythological Thinking in the Dialogic Structure of Dostoevsky’s Discourse (The Brothers Karamazov)],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Saraskina, L. V. (2001) “F M Dostoevsky I “Vostochnyi vopros” [F M Dostoevsky and the “Eastern Question”],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Schmid, Wolf (1973) Der Textaufbau in den Erzählungen Dostoevskijs, Beiheft zu Poetica, Karl Maurer (ed.), Heft 10 (München: Wilhelm Fink).

Stepanian, K. A. (2001) “Smert’ i voskresenie, Bytie i nebytie v romanakh Dostoevskogo [Death and resurrection, Being and Non-Being in Dostoevsky’s Novels],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Stuchebryukhova, Olga (2005), “The Subaltern Syndrome and Dostoevsky’s Quest for Authenticity of Being,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 5.

Тарасова, Н. А. (2005), “Проблема понимания в герменевтике и текстологии (на материале рукописей Достоевского),” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 5.

Тарасова, Н. А. (2002-2003) “Проблема установления текста Дневника писателя Ф. М. Достоевского 1876 г.” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Terrell, Nicholas (2006) “Soap Bubbles and Inertia: The Underground Man’s Dependence on Rhetoric, Narrative Frameworks and Scepticism as a Syndrome of Secular Idealism,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 7: 1-29

Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, “Dostoevsky Studies in Australia 1956 – 2012” in: Sobranie sochinenij i pisem F. M. Dostoevskogo, 2-e, ispravlennoe i dopolnennoe izdanie. Sbornik, posviashchennyi teme “Vospriatie i izuchenie tvorchestva F. M. Dostoevskogo v mire”. Glavnyi redaktor Nina Fedotovna Budanova, (StPeterburg: “Nauka”, 2013).

Vladiv, S. B. (1989) “Dostoevsky’s Major Novels as Semiotic Models,” Dostoevsky Studies 9: 157-162.

Vladiv, S.B. (1980) (Guest Editor), Melbourne Slavonic Studies. Dostoevsky Commemorative Number. No. 14.

Vladiv, S. B. (1979) Narrative Principles in Dostoevskij’s Besy: A Structural Analysis (Berne; Frankfurt; Las Vegas: Peter Lang).

Vladiv-Glover, `Slobodanka M. (2019) Dostoevsky and the Realists: Dickens, Flaubert, Tolstoy. (New York: Peter Lang), 215 pp.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2011-2012), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 12-13 (2011[2012]-2012) In press.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2011) “The Accidental Family in The Adolescent and Wittgenstein’s ‘Family Relations’: The Novel as Model of Meaning,” in: Aspects of Dostoevsky’s Poetics in the Context of Literary-Cultural Dialogues. Editors: Katalin Kroó, Géza S. Horváth, Tünde Szabó. Volumne 3 Dostoevsky Monographs Series.(Sankt-Peterburg:”Dmitrii Bulanin,” 2011), pp. 59-74.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2009-2010), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 10-11 (2097[2010]-2010) (104 pp)

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2010) The Poetics of Realism: Dostoevsky, Flaubert, Tolstoy. Trans. into Serbian. (Belgrade:”Ariadna”/ Pancevo: Mali Nemo”), 182 pp..

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2007-2008), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 8-9 (2007[2010]-2008[2010]) (89 pp)

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2006), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 7 (2006) (106 pp)

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2005), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 6 (2005) (109 pp)

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2005), “Tolstoy’s Mikhailov, The Painter of Anna’s Portrait, and Constatin Guys, Baudelaire’s Painter of Modern Life”, Facta Universitatis Series Linguistics And Literature, Vol. 3, No 2, 2005, Vol.3, No 2, 2005 pp. 151 – 160 UDC 821.161.1.09.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2004), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 5 (2005) (216 pp)

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2002-2003), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 3-4 (2002-2003) (228 pp)

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2003) “Speech as the Sacred in The Brothers Karamazov,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 3-4 (2002-2003), pp. 93-112.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2002-2003) “Speech and Being in The Brothers Karamazov,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2002-2003) “Speech and Being in The Brothers Karamazov.” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4: 83-112.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2001), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 2 (2001) (152 pp) Special Issue on “Dostoevsky and the Problem of Dialogue in Contemporary European Thought.” Guest Editor: Natalia Pecherskaya (St.Petersburg School of Religion and Philosophy).

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2001) , Romani Dostojesvkog kao diskurs transgresije i požude [Dostoevsky’s Novels as Discourse of Desire and Transgression], (Belgrade. “Prosveta”), 215 pages.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (ed.) (2000), The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review. Vol. 1 (2002-2003) (166 pp) Inaugural Issue.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (2000) “Russia’s Political Unconscious in The Possessed: Dostoevsky’s New Phenomenology of History and Representation,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 1: 11-28.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1999) “Sakral’noe v Brat’iakh Karamazovykh: veroispovedanie ili fenomenologiia soznaniia?” Dostoevskii i mirovaia kul’tura: Al’manakh, vol. 12: 7-12.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1998) “What Does Ivan Karamazov Know? A Reading Through Foucault’s Analytic of the Clinical Gaze,” in Rudolf Neuhauser (ed.) Polyfunktion und Metaparodie: Aufsatze zum 175. Geburtstag von Fedor Michailovic Dostojevskij: Dostoevsky Studies Supplements, vol 1 (Dresden-Munchen: Dresden University Press), pp.189-207.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1998) “What Does Ivan Karamazov ‘Know’? A Reading Through Foucault’s Analytic and ‘Clinical’ Gaze,” in Rudolf Neuhauser (ed.) Polyfunktion und Metaparodie. Aufsätze zum 175. Geburtstag Fedor Michajlovič Dostojevskijs (Dresden: Dresden University Press), pp. 189-207.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1997) “The Body and Violence: The Subject of Knowledge in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov”, in: Foucault: The Legacy, ed. by Clare O’Farrell (Queensland U of Technology, 1997): 46-57

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1996), “The Bourgeois and Citizen Alyosha Karamazov,” Australian Slavonic and East European Studies (ASEES), Vol 10, No. 2 (1996):165-67.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1995) “What Does Ivan Karamazov ‘Know’? A Reading Through Foucault’s Analytic of the ‘Clinical’ Gaze,” New Zealand Slavonic Journal: 23-44.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1993) “Dostoevsky, Freud and Parricide: Deconstructive Notes on The Brothers Karamazov,” New Zealand Slavonic Journal: 7-34.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1989), “Dostoevsky’s Positively Beautiful Man and the Existentialist Authentic Self: A Comparison,” Canadian American Slavic Studies, Vol 23, No. 3 (Fall 1989): 313-329.

Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka M. (1989), “Dostoevsky’s Major Novels as Models of Meaning,” Dostoevsky Studies (Journal of the International Dostoevsky Society), Vol 9, No.1 (1989): 157-162.

Woodford, M. (2001) “Kommentarii k snu glavnogo geroia v rasskaze F M Dostoevskogo ‘Gospodin Prokharchin’ [Commentary on the Dream of the Hero in Dostoevsky’s Story ‘Mr Prokharchin’],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Живолупова, Наталья (2002-2003) “Исповедь антигероя: от Достоевского к Михаилу Агееву (проблема жанра),” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Zhivolupova, Natalia V. (2001) “Drugoi v khudozhestvennom soznanii Dostoevskogo i problema evolutsii ispovedi antigeroia [The Other in Dostoevsky’s poetics and the evolution of the confessional form of the anti-hero],” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol 2.

Zink, Andrea (2006) “What is Prostitution Good For: Dostoevsky, Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy and the ‘Woman Question’ in Russian Literature,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vol. 7: 93-106.

Zohrab, Irene (2002-2003) “Ulrich’s Confessional ‘Third Sex’ Theory and the Creation of The Possessed,” The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4.

Zohrab, Irene (2002-2003) “Mann-Männliche Love in Dostoevsky’s Fiction (An Approach to The Possessed): With Some Attributions of the Editorial Notes in The Citizen.” (First Instalment). The Dostoevsky Journal: An Independent Review, vols. 3-4: 113-226

FOUNDER OF DOSTOEVSKY STUDIES IN AUSTRALIA

CO-FOUNDER OF THE INETRNATIONAL DOSTOEVSKY SOCIETY

Dmitry Vladimirovich Grishin

Dmitry Vladimirovich Grishin (1908-1975) was a Russian university academic and author who was an internationally recognised authority on the Russian writer and philosopher F.M. Dostoevsky who primarily taught in Australia at the University of Melbourne.

He was born on 12 September 1908 at Kamyshin, on the Volga River, in the Tsaritsen Region in Russia. He was the eldest in a family of five with his father, Vladimir Grishin, a schoolteacher and farmer who owned a flourmill, small orchard and apiary, and his wife Lubov, née Alabuseva. In 1927 his father was arrested as a kulak; his wife and four younger children were sent to Siberia. Dmitry, a student at the Pedagogical Institute, Saratov, escaped their fate, but his academic career suffered a setback. Graduating in 1935, he became a schoolteacher and part-time lecturer in medieval Russian literature at the institute.

In Moscow on 9 December 1940 Grishin married Natalia Luzgin, a science teacher and a daughter of an aristocrat and classics professor. He taught Russian literature at the University of Moscow and was awarded the title Kandidat filologicheskikh nauk for his thesis on ‘Early Dostoevsky’. When the university staffs were evacuated from Moscow, Grishin was appointed acting-head of the Russian literature department in Elista, capital of the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

During the blitzkrieg of 1942 he and his wife were taken prisoner, placed in a concentration camp and later assigned to work for a dentist in Berlin. They survived allied bombing and on one occasion were buried in the debris of a demolished house. In March 1945 they fled to Bad Nevenahr and thence to Emden where they obtained an entry visa to Australia.

On 23 September 1949 they arrived in Melbourne. At Bonegilla immigrant camp, Grishin organized protests about substandard living conditions. While employed as a laboratory-assistant at Monsanto Chemicals (Australia) Ltd, Footscray, he began working as a part-time tutor in the department of Russian language and literature at the University of Melbourne. In 1954 he was naturalized.

Dmitry Grishin moved through the university ranks of full-time tutor (1953), senior tutor (1954), lecturer (1956), senior lecturer (1962) and reader (1970). Meanwhile, he resumed his research. In 1957 he was awarded a Ph.D. for his thesis on Dostoevsky’s Diary of a Writer. He published a series of books in Russian: Dostoevsky’s Diary of a Writer (1966), Dostoevsky: The Man, Writer and Myths (1971) and The Young Dostoevsky (posthumously, 1977); his collection of Dostoevsky’s aphorisms was published in Paris in 1975.

An indefatigable participant in international congresses, in 1968 at the 6th International Congress of Slavists, Dr Grishin started to organise Dostoevsky scholars from various countries to create an International Society devoted to the study of the life and works of F.M. Dostoevsky in time for the 150th anniversary of his birth in 1971. Coordinating with scholars from fourteen countries, Dr Grishin formed the International Dostoevsky Society with himself as founder and president, Professor Nadine Natov (USA) as the Executive Secretary and Professor Rudolf Neuhäuser (Canada) as Coordinator. In September 1971, in Bad Ems in Germany, the first symposium of the International Dostoevsky Society was held to commemorate the anniversary of the writer’s birth.

In 1973 Dr Grishin retired from the university. He died of coronary vascular disease on 19 September 1975 at his North Coburg home in Melbourne, Australia.

Emeritus Professor Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA

Australian National University

Art critic at Canberra Times

Guest Curator, National Gallery of Victoria

CV Dmitry Vladimirovich GRISHIN

1908, born 12 September 1908, Kamyshin, on the Volga River, in the Tsaritsen Region in Russia

1935, graduated from the Pedagogical Institute, Saratov

1940, 9 December married Natalia Luzgin

1940, appointed to teach Russian literature at the University of Moscow

1940, University of Moscow awarded Kandidat filologicheskikh nauk for his thesis on ‘Early Dostoevsky’

1942, captured by the Nazis and placed in forced labour and concentration camps for the duration of the war

1949, 23 September, arrived in Melbourne, Australia, on board General W C Langfitt, and billeted at Bonegilla immigrant camp

1953, appointed full-time tutor at the University of Melbourne, Department of Russian Language and Literature

1954, naturalised, granted Australian citizenship

1954, appointed senior tutor at the University of Melbourne, Department of Russian Language and Literature

1956, appointed lecturer at the University of Melbourne, Department of Russian Language and Literature

1957, was awarded a PhD from Melbourne University for his thesis on Dostoevsky’s Diary of a Writer

1962, appointed senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne, Department of Russian Language and Literature

1968, at the 6th International Congress of Slavists, Dr Grishin, as president of the organising committee of the International Dostoevsky Society, commenced organising Dostoevsky scholars from various countries to create the International Dostoevsky Society

1970, appointed Reader (Associate Professor) at the University of Melbourne, Department of Russian Language and Literature

1971, September, Bad Ems in Germany, the first symposium of the International Dostoevsky Society was held where he was elected as the first vice-president of the Society

1975, died 19 September in Melbourne